HTA Dossiers: A Guide to Submissions for NICE, CADTH & ICER

Executive Summary

Health technology assessment (HTA) dossiers are comprehensive evidence packages that pharmaceutical manufacturers assemble to support reimbursement and access decisions by HTA agencies. In major jurisdictions, such as the UK (NICE), Canada (CADTH/Canada’s Drug Agency), and the US (ICER), these dossiers typically include systematic reviews of clinical evidence, detailed cost-effectiveness and budget-impact analyses, and contextual information (e.g. on patient perspectives and comparator therapies). Although formats vary, all three agencies require sponsors to present the best available clinical data (often via systematic literature reviews of randomized trials and observational studies), an economic model demonstrating value, and supporting documents (e.g. comparators’ reimbursement status). NICE provides fixed templates (e.g. a Submission Template, Decision Problem form, Budget Impact template, and Patient Summary) that companies must use ([1]) ([2]). CADTH likewise provides structured templates – most notably a Sponsor’s Summary of Clinical Evidence with specified sections on background, systematic review, extension studies, indirect comparisons, and evidence gaps ([3]) ([4]) – along with guidance that only one base-case economic model (e.g. cost-effectiveness analysis) be submitted per indication ([5]). ICER, though not a regulatory body, conducts independent evidence reviews (its Value Assessment Framework) and actively engages manufacturers: companies can submit unpublished (“in-confidence”) clinical or economic data early in the scoping phase, and provide detailed inputs (e.g. patient survey data, dosing scenarios) to help ICER refine its models ([6]) ([7]).

Access teams must plan and build these dossiers well in advance of national launches. The process typically starts during clinical development, with horizon-scanning and early “scientific advice” interactions to define the scope (patient group, comparator, outcomes). Closer to launch, multidisciplinary teams (medical, HEOR, regulatory, market access) conduct systematic reviews (searching databases by pre-specified strategy), extract and appraise all relevant evidence, and develop or adapt economic models (often Markov or partitioned-survival models) reflecting the agency’s reference-case assumptions. They also compile epidemiologic data (for denominators and quality‐of‐life weights), implement sensitivity and scenario analyses, and generate outputs (incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), QALY gains, budget-impact projections, probabilistic sensitivity analyses, etc.). Because HTA agencies (NICE, CADTH, ICER) often release detailed technical requirements, teams must ensure all components meet the specified format and style. In practice, this requires substantial project management: internal and external experts (e.g. health economists, methodologists, clinicians) perform iterative drafts, address agency “points of clarification,” and finalize a robust evidence submission by the strict deadlines (for example, NICE STAs require submission 56 days after NICE’s invitation ([8]), within a ~35-week appraisal timeline ([9])).

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the structure and content of HTA evidence dossiers for NICE, CADTH, and ICER. We examine each agency’s submission process, required documents, and evidentiary standards; compare how dossiers differ (and overlap) across jurisdictions; and discuss how industry access teams compile, review, and refine these dossiers. Multiple perspectives are included: official guidelines, independent analyses of past submissions, and real-world examples of submission components. The discussion covers historical context (the origins of these HTA bodies and evolving methods), current requirements (systematic review standards, economic modeling expectations, patient involvement), and future trends (e.g. expanded use of real‐world evidence and international alignment). All claims and descriptions are supported by up-to-date sources, including official NICE and CADTH manuals, ICER guidance documents, peer-reviewed studies, and newsletters. Statistical data (e.g. numbers of appraisals, typical thresholds) and expert commentaries illustrate key points. Finally, we consider implications for manufacturers (e.g. importance of transparent methods, early planning) and for the HTA field (e.g. moves toward global dossier harmonization, adaptive access mechanisms).

Introduction and Background

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agencies evaluate new medicines to inform coverage and reimbursement. They balance clinical benefit, cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and societal values. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has statutory authority: NHS England must fund treatments recommended in NICE technology appraisals ([10]). NICE conducts Single Technology Appraisals (STAs) (for one drug/indication) and, for ultra-rare treatments, Highly Specialised Technologies (HST) appraisals. In Canada, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (now the “Canada’s Drug Agency”) operates national reviews. Historically, non-oncology drugs underwent the Common Drug Review (CDR) and cancer drugs the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) ([11]); both processes provide non-binding reimbursement recommendations to public drug plans (except Quebec). In the US, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) is an independent nonprofit that publishes transparent value assessments; its guidance affects private payers and policy despite having no formal regulatory power. Each organization has developed structured processes requiring manufacturers to supply evidence packages – often called “dossiers.”

HTA dossiers serve similar purposes: they document all evidence the manufacturer considers relevant to clinical effectiveness and value. Typically they include (1) a systematic review and synthesis of efficacy/safety data, (2) a health-economics analysis (cost-effectiveness model), and (3) contextual information (budget impact, patient perspectives, comparator details, etc.). However, each agency has distinct templates and expectations. NICE provides formal submission templates and procedural manuals; CADTH issues a reimbursement review procedures guide and sponsor templates; ICER offers a Manufacturer Engagement Guide and openly discusses its evidence framework. Over time, these dossiers and guidelines have become more detailed. For example, NICE’s STA manual (updated 2022–2025) specifies that every clinical trial relevant to the scope must be included (with company chief officer attesting to full disclosure ([2])) and mandates accessible reporting of all evidence ([12]). Similarly, CADTH recently introduced a five-section “Sponsor’s Summary of Clinical Evidence” template to standardize what clinical data sponsors present ([3]).

The history of manufacturer submissions at NICE dates to 2005, when STAs were introduced to shorten appraisal timelines. A seminal study of early STA submissions found widespread variability in quality: common issues included missing analyses, inconsistent reporting, and confusion over the “decision problem” ([13]). These findings triggered many improvements in guidance and industry practice.Today’s NICE template and technical guidance require systematic reviews, fully specified comparators (as defined in the appraisal’s scope), and explicit modeling methods ([14]) ([15]). Likewise, CADTH’s processes have evolved. Older CDRs permitted multiple summary submissions; recent policy mandates only one base-case economic model per indication ([5]) and stronger literature review standards ([16]). In parallel, ICER has sharpened its Value Assessment Framework (VAF) and engagement procedures, emphasizing transparency and inviting manufacturers to share unpublished data (as “academic-in-confidence” studies or pricing information) early in the review ([6]) ([7]).

Current State of HTA Dossier Structure: Despite differences, there is broad convergence in evidence types: all require comparative clinical data (usually from one or more pivotal trials vs. standard of care), preferably including overall survival or QALYs. When head-to-head data are lacking, companies must perform indirect comparisons (network meta-analyses or naive adjustments) – NICE committees expect all such analyses to be transparently reported, and CADTH’s new template explicitly asks sponsors to summarize and attach any indirect comparison reports ([4]). Patient-reported outcomes (quality-of-life, utilities) are crucial inputs to each model. Each HTA typically has a “reference case” for economic evaluation: NICE’s is a health- and social-care perspective with QALYs and a £20,000–£30,000/QALY threshold; CADTH’s base case is healthcare-system perspective (with optional scenario analyses) and no fixed threshold; ICER often uses a U.S. payer perspective and a willingness-to-pay range (commonly $100,000–$150,000 per QALY, with special modifications for very rare diseases ([17])). Accordingly, the health economics section of a dossier must describe model structure, key parameters (costs, utilities, transition probabilities), assumptions (time horizon, discounting), and results (including sensitivity/scenario analyses). NICE and CADTH require submission of the actual model (in Excel or similar) for technical review, with documentation of each parameter source. ICER typically conducts its own modeling but will request data and even model files from manufacturers to ensure accuracy.

The organization of an HTA dossier is usually sequential: first, contextual sections (drug description, treatment pathway, epidemiology, comparator justification); then clinical evidence (study evidence, meta-analyses, outcomes tables); then economic evidence (model methods/results); and finally appendices (search strategies, full references, model files). Agencies provide submission templates or outlines. For instance, NICE’s STA submission template (Word form) covers major headings including: Population and Subgroups, Interventions and Comparator, Outcomes, Clinical Effectiveness Evidence, Economic Model etc ([1]) ([14]). CADTH likewise specifies that the Sponsor’s Summary must include sections like Background, Systematic Literature Review, Extension Studies, Indirect Comparisons, Addressing Evidence Gaps ([3]) ([4]). In practice, access teams also include essential tables (e.g. characteristics of included studies, results summaries, model outcomes, cost breakdowns) and graphical outputs (cost-effectiveness planes, acceptability curves).

Finally, we outline how these components are assembled in practice. Typically, a manufacturer’s global market-access team will begin drafting the dossier long before regulatory approval. The process may involve preliminary “horizon scanning” at phase II/III to anticipate HTA questions, followed by explicit advice meetings with agencies (e.g. NICE Scientific Advice, CADTH pre-submission meetings) to agree on comparators, endpoints, and analysis plans. Closer to launch, dedicated project managers coordinate the evidence generation and document drafting. This often entails outsourcing systematic reviews and economic modeling to specialized firms or academic groups; such independent reviews (similar in role to NICE’s ERG but conducted pre-submission) can help ensure robustness. The final submission undergoes multiple rounds of internal review for consistency (e.g. the clinical evidence should match what the model uses) and clarity before the official deadline. Notably, NICE requires the company’s medical director to sign a statement that all relevant trial data have been disclosed ([2]), reinforcing the need for meticulous internal tracking of data sources. After submission, agencies may send queries; NICE’s Evidence Review Group (ERG) typically has 21 days to request clarifications, and the company must respond with any additional analyses.

In the following sections, we delve into each element of this process with great detail, drawing on official NICE and CADTH manuals, ICER guidelines, peer-reviewed analyses, and practical case examples. We use empirical studies where available (e.g. [53]’s analysis of early STA submissions) and cite specific numeric data (e.g. deadlines, timeline lengths, threshold values) to ground our descriptions. The goal is to provide a comprehensive resource for understanding exactly “what goes into” an HTA dossier and how it is built.

NICE HTA Dossiers: Structure and Submission Process

Overview of the STA/HST Process

NICE guidance is developed through a formal appraisal process. Following a new drug’s marketing authorization (MA), NHS England may refer the technology to NICE for a Single Technology Appraisal (STA), typically to achieve guidance within ~3 months of MA ([18]). The process is divided into stages (Figure 1): scoping, evidence submission, evidence review, and final decision. During scoping, NICE consults stakeholders and finalizes the Decision Problem (target population, comparator, outcomes). Shortly after, NICE issues an “invitation to participate” to the manufacturer and other stakeholders, marking the official start of the evidence submission phase ([15]). The company is then given a deadline (56 calendar days for STAs ([8])) to submit its evidence dossier.

Key timeline benchmarks (from NICE’s 2025 process manual): companies have 56 days after the invite to complete an STA evidence submission, and the Technology Appraisal Committee typically meets about 35 weeks (8–9 months) after referral ([8]) ([9]). During this time the Evidence Review Group (ERG) critically appraises the submission. If the submission is incomplete or inconsistent with the scope, the ERG can issue a clarification letter within 21 days, and the company has 14 days to respond ([19]) ([20]). Ultimately, a manuscript (the draft guidance) is prepared roughly 2–3 months after submission, followed by a 4-week Appeal window. Thus, from submission to final guidance is on the order of 6–8 months under normal STA timelines (HST appraisals have similar but slightly different timeframes). Recent process updates allow some flexibility (e.g. coordinating appraisals of multiple products concurrently ([21])), but the basic requirement remains: the company must submit a comprehensive evidence package by the set deadline.

NICE Submission Components

NICE provides standardized templates and forms for company submissions. On the NICE website, the relevant page lists these “Company submission templates” including: a cost-utility submission template (in Word), a Decision Problem Form, a Budget Impact Analysis (BIA) template, and a Summary of Information for Patients ([1]). All submissions must be compatible with NICE’s process (e.g. plain fonts, accessible documents). The submission itself must be comprehensive: NICE explicitly warns that all evidence submissions and other information supplied as part of the evaluation can be published on the NICE website and must meet accessibility standards (Section 5.3.8) ([12]). Companies are even encouraged to make their submissions public on their own websites after sending them to NICE ([12]). A signed declaration must accompany the submission, confirming that every relevant clinical trial data has been disclosed (with the medical director’s signature under section 256 of the Companies Act) ([2]). Companies must also allow NICE to request unpublished trial data from regulators if needed ([22]).

In practice, a NICE evidence dossier typically comprises:

- Decision Problem Form: This document (provided by NICE) succinctly re-states the final scope and decision problem. The manufacturer uses it to confirm or refine the scope elements (population definition, comparators, outcomes). NICE explicitly allows the company to discuss the decision problem with NICE before submission ([23]). If the company suggests any changes, NICE may consider them (but will not re-open scoping to add new comparators ([24])).

- Clinical Evidence Section: A complete summary of the clinical data, usually organized as follows:

- Trial Flow Diagram and Tables: PRISMA-style flowchart of study selection, and tables listing all comparative studies (arm details, outcomes). These often include indirect comparisons (Network Meta-Analyses, NMA) if direct comparisons with the comparator are absent. NICE requires that if an NMA or any indirect comparison is included, the full technical report or appendices must accompany the submission (detailing assumptions and results) ([4]).

- Systematic Review Methods: Description of literature search strategy (databases, date range, inclusion criteria), risk-of-bias assessment, and data abstraction. (Although NICE templates may integrate narrative review text, the underlying methods adhere to systematic-review standards.) While NICE’s own manual does not explicitly quote PRISMA guidelines, industry best practice is to follow systematic review methodology. In fact, CADTH now explicitly requires a systematic review and has a template section for it ([16]), and NICE STA submissions are expected to similarly include systematic identification of evidence (as noted in a BMJ Open study of submissions ([14])).

- Results (Efficacy & Safety): Presentation of trial findings for key outcomes (e.g. survival, response rates, quality-of-life). This often includes subgroup analyses if relevant. Companies must present intention-to-treat results and any sensitivity/best-case data. Safety data (adverse events) are also summarized.

- Consistency Checks: NICE’s ERGs look for internal consistency (the clinical data used in the model should match what the text describes) ([13]). Thus companies provide cross-referenced tables (e.g. referencing model inputs).

- Economic Evidence Section: The heart of the submission is the economic model. NICE requires a cost-utility analysis (unless a special “cost-comparison” process is invoked) ([25]). The key components:

- Model Specification: A detailed description of the model structure (often Markov states or trial-based partitioned survival), time horizon, cycle length, perspective (NHS/PSS), discount rates (standard NICE: 3.5% per annum for costs and QALYs). The department explicitly asks which software will be used (Section 5.5.15) ([26]). Companies typically use Excel or specialist software (sometimes TreeAge, R, etc) and submit the model as an electronic file. If cost comparison (for very minor differences), a simpler template is provided, but for STAs companies must use the detailed STA template ([25]).

- Parameters: Sources and values for all inputs—treatment effects (hazard ratios, transition probabilities), utilities (generally EQ-5D-based, as per NICE’s reference case), resource use and costs (from UK sources). Sensitivity of results to uncertain parameters is addressed via deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis.

- Base-Case ICER: The result (incremental cost per QALY gained) under the company’s preferred assumptions. NICE expects this to be clearly stated.

- Scenario/Subgroup Analyses: For example, the submission might show results excluding a specific trial (with justification), or modeling a patient access scheme. NICE allows “commercial access agreements” to be discussed at submission ([24]).

- Budget Impact Analysis (BIA): Separate template (usually Excel) projecting the financial impact on the NHS given uptake forecasts. This includes drug pricing list, patient population size (from epidemiology data), and other costs. The BIA template is required alongside the main evidence ([1]).

- Patient Information: A “Summary of Information for Patients” written in lay language, required by NICE ([1]). Although primarily for patient groups, it must also be submitted by the company.

- Appendices: Full references, search strategies (so others can replicate), detailed tables (e.g. all utility values used, all data points in the model). The NICE manual instructs that any cited journal articles must be included in full if quoted (or the company must have copyright permission) ([2]).

All submissions are sent to NICE’s project manager and made accessible to a designated Evidence Review Group (ERG) – usually an external academic team funded by NICE (e.g. in the NIHR HTA Programme) – which produces an independent critique. The ERG and clinical leads then explore if the submission fully addresses the scope . If not, NICE issues clarification requests. Common issues noted in the literature include internal inconsistencies between clinical and economic sections, inappropriate or missing analyses, or unclear methodology ([13]). Manufacturers are advised to follow NICE’s templates closely to avoid such problems.

The NICE templates and guidance are publicly available on the NICE website. For example, NICE’s STA methods manual (PMG36, updated Jan 2022, current) can be read online, and the company submission template is downloadable as a Word file ([1]) ([2]). These resources offer explicit instructions on what goes in each section. In short, a strong NICE dossier must transparently present all relevant clinical trials and a fully specified economic evaluation, following NICE’s reference case. The sponsor is expected to act essentially like an “independent evidence provider” (even though they are the drug developer), offering whatever data they have while being rigorously transparent about methods.

NICE Dossier Preparation: Practical Considerations

Planning and Timelines: NICE encourages early engagement. On its “Planning Your Submission” page, NICE advises planning to achieve TA guidance by 3 months post-approval ([18]). This implies working backwards from the target MA date. In practice, companies often coordinate with regulators and pricing bodies (the UK well-known processes are the Early Access to Medicines scheme (EAMS) and Patient Access Schemes), but parallel to that, parallel track NICE. Companies may formally notify NICE of their upcoming submission (a so-called “horizon scanning” alert) or even request a pre-submission dialogue.

Once NICE’s scoping is final, the company typically has about two months to finalize the submission (56 days after invite for STAs ([8])). In that window, work is often already advanced: systematic searches have likely been run, data extracted, and models developed earlier. Still, the actual drafting is intensive. A typical assembly plan might look like: (a) initial draft of the Decisional Problem outline (the strategy of evidence), (b) finalize search strategy and begin data compilation, (c) draft clinical section framework, (d) finalize economic model base case, (e) populate submission template (fill Word document with sections), (f) prepare BIA spreadsheet and patient info sheet, (g) internal reviews and sign-offs, (h) delivery. Concurrently, the company often arranges a “Technical Engagement” meeting with NICE (around 2–3 weeks before submission) to check that the scope is understood and the approach is satisfactory (as per NICE guidance, companies can request extra engagement time ([27])).

Team Structure: An access team typically includes health economists, epidemiologists, statisticians, physicians with disease expertise, and regulatory specialists. Often a lead consultant (or internal project leader) coordinates the writing teams. Some specialists focus on the systematic review (ensuring exhaustive literature search and transparent reporting), while others lead model programming. Due to the workload, many firms outsource elements (e.g. contracting a university or CRO to perform a network meta-analysis, or a model programming shop to implement a Markov model). Throughout, oversight is needed to maintain consistency: for example, the “clinical effect” inputs in the model must match those summarized in the clinical evidence tables. The BMJ Open study by Kaltenthaler et al. highlighted that ERGs often find “internal inconsistencies” (e.g. the values differ) ([13]), so industry teams create rigorous cross-check procedures (peer review of tables and model inputs, etc.).

Compliance and Confidentiality: Before accessing NICE’s confidential documents (draft assessment report, submission documents from others), all stakeholders must sign a confidentiality undertaking ([2]). The company’s dossier often contains commercially sensitive information (e.g. price proposals, market uptake forecasts). NICE allows companies to mark parts of their submission as confidential; in that case, two versions must be provided (one public, one marked confidential) ([28]). The recent CADTH updates on confidentiality are similar: they provide a clear table of what can be redacted (price vs. clinical data) ([29]). Companies usually handle this by clearly flagging sections (e.g. “Confidential: price per patient”).

Evidence Scope and Innovation: HQ guidance often encourages including not only positive trial data but also any unpublished or negative evidence. For example, NICE requires that the company declare awareness of all trial data relevant to the scope and provide it ([2]). If new data emerges during the appraisal (e.g. an open-label extension trial ends after the submission deadline), the company may submit it via the clarification process. This is partly why timelines are tight – late-breaking evidence can be critical. For breakthrough therapies, NICE also sometimes applies alternative frameworks: e.g. an “end-of-life” consideration or a different threshold, if the drug meets certain criteria. Companies anticipating this should prepare justification statements.

Common Pitfalls: The literature on submission quality highlights frequent problems to avoid. Some recurrent issues (from the BMJ Open study ([13]) and NICE ERG experiences) include:

- Poorly defined subpopulations or comparators (leading to “decision problem” mismatches).

- Omitting a relevant analysis (e.g. not performing a multi-way sensitivity when limits are clear).

- Not explaining why an analysis is not done (e.g. skipping indirect comparison without justification).

- Fragmented narrative (e.g. claiming something in the text but not showing data).

- Overly optimistic utilities or costs not aligned with NHS standards.

Being aware of these, companies often pre-review their draft dossiers against fixed checklists (like NICE’s Appendix 5 “Checklists for Preparing Applications” ([30])) to ensure completeness. The NICE submission templates themselves prompt for nearly all required elements, which helps avoid omissions.

NICE Submission Templates (Table 1)

| Component | NICE Submission (UK) |

|---|---|

| Required Forms / Templates | Detailed Word Submission Template with sections (clinical/economic); Decision Problem form; Budget Impact Excel template; Summary for Patients ([1]) ([2]). |

| Clinical Evidence | Systematic review of all trials and studies; inclusion/exclusion criteria; risk-of-bias assessments; detailed tabulated results (efficacy, safety); discussion of subgroups. |

| Comparators | As defined in the final scope; justification of choice; report of any off-label use if relevant; list reimbursement status of comparators if asked (not formally required by NICE, but often prepared informally). |

| Indirect Comparisons (NMA) | If no head-to-head trial exists, include an NMA. Full methods and technical report should be provided. If none, explain why (lack of data or relevance) ([4]). |

| Economic Model (CEA) | One base-case cost-utility model (per CTA); in NHS perspective; include QALY calculations; provide model files (NICE expects companies to inform which software ([31])). Sensitivity & scenario analyses required. |

| Cost and Utility Inputs | NICE reference case prefers EQ-5D utilities and UK costs. All input sources must be cited. Utilities from clinical trials or literature; costs from national tariffs or literature. |

| Budget Impact (BIA) | Excel model projecting drug cost over 5 years (or other timeline); includes population estimates and uptake; template provided by NICE ([32]). |

| Patient Perspective | Lay summary using NICE template (patient-friendly); plus company may include patient preference data if relevant. |

| Administrative | Cover letter, sign-off statements (disclosure statement by MD ([2])), list of contents, list of abbreviations. |

Table 1. Major components of a NICE technology appraisal submission. The evidence submission must be aligned with the final scope and is structured according to NICE templates ([1]) ([2]). Contrary to some HTA bodies, NICE produces separate reports (e.g. ERG report, appraisal determination) but here we focus on the company’s submission package.

CADTH (Canada’s Drug Agency) Dossiers

Overview of CADTH Process

In Canada, the national HTA for drugs is handled by the Canada’s Drug Agency (formerly CADTH). It operates two main processes: the Common Drug Review (CDR) for non-oncology drugs, and the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) for cancer therapies ([11]). These processes are advisory: they produce reimbursement recommendations (and funding guidance algorithms) for the public drug plans of all provinces and territories except Quebec. Unlike NICE, CADTH’s decisions are not legally binding, but provincial plans generally follow them.

The CADTH process is similar in structure to NICE: after receiving a submission ("application") from the sponsor, CADTH conducts a critical review (clinical and economic), and a multi-stakeholder expert committee deliberates to issue guidance. Manufacturers can often submit dossiers before regulatory approval to align timelines. Unlike NICE’s single TA committee, CADTH uses an expert committee (Canadian Drug Expert Committee, CDEC, or cancer-specific pERC) for recommendations, with an industry and non-industry co-chair. Broadcast patient and clinical expert input is also gathered.

Eligibility and Timing: Notably, the CADTH submission can occur before or after regulatory MA¶. If submitted in advance, the process runs in parallel so that guidance is ready soon after approval. Table 4 of CADTH’s HTA procedures notes that applications can be made before approval to expedite the review ([33]). CADTH’s internal target timeline for reviews is on the order of 6–7 months ☆. Indeed, an environmental scan found CADTH’s CDR/pCODR had typical total timelines ~25 weeks, compared to ~35 weeks for NICE ([9]). In practice, CADTH posts public calls for applications with set deadlines (for example, a “Drug Review Submission Deadline”). During 2023, CADTH has been streamlining processes (e.g. introducing “time-limited” recommendations for provisional funding, and considering unsponsored reviews where no manufacturer applies ([34])), but the core submission requirements remain well-defined.

CADTH Submission Components

CADTH requires a formal Application from the sponsor (manufacturers or an eligible supporter). Key components of a CADTH drug reimbursement submission include:

- Cover Letter & Administrative Forms: Including a completed Application intake form, contact information, and signed authorization.

- Sponsor’s Summary of Clinical Evidence: This is a structured template (Word) that CADTH introduced in 2022 (finalized for implementation in 2023) to standardize clinical evidence submissions ([3]). It contains five sections:

- Background Information – drug mechanism, indication, place in therapy, references.

- Systematic Literature Review (SLR) – methods and results. The sponsor must conduct and report a full SLR according to the template’s instructions ([16]). This section typically includes PRISMA-style diagrams and lists of included trials. CADTH expects modern SLR methods (duplication of searches, quality assessment, etc.).

- Extension Studies – summary of any long-term extension trial data (important in chronic diseases). Full source docs (e.g. CSR excerpts) should be appended. If no extension data exist, the section is retained (not removed) and noted as “None available” ([35]).

- Indirect Comparisons – summary of all NMAs or indirect analyses the sponsor has performed. The template instructs sponsors to provide the complete technical reports for these comparisons ([4]). If no comparative trial data exist, sponsors must explain why indirect comparison is infeasible. This ensures transparency of methods and prevents selective reporting.

- Evidence Gaps – the sponsor identifies and summarizes any additional studies addressing gaps in the primary evidence (for instance, observational studies in populations not covered by trials) ([36]). CADTH explicitly allows the sponsor to submit such supplementary data (provided in accordance with CONSORT or STROBE reporting), which the agency will consider on a case-by-case basis ([37]). This helps CADTH address uncertainties in case-trial evidence.

After these sections, sponsors must also submit a bibliographic file (Reference Information Systems format) containing all references cited in the summary ([38]). This allows CADTH analysts to import literature easily. (This RIS requirement is a recent innovation noted in the 2022 updates ([38]).)

-

Clinical Study Reports and Key Publications: Full CSRs for pivotal trials (possibly redacted) or equivalent (published paper + appendices). All trials included in the sponsor’s summary should be documented. CADTH advises providing complete documentation if possible.

-

Reimbursement Status of Comparators Template: A required form (Word) listing how comparator drugs are funded in various jurisdictions. In recent news, CADTH noted this template was updated for plasma protein therapies ([39]). The purpose is to inform committee about existing funding (on a named patient basis, etc.) for comparators.

-

Economic Evidence: Usually submitted as a separate Economic Model Submission (EMS). The sponsor provides a pharmacoeconomic model (cost-utility, unless cost-minimization is justified for identical therapies) and accompanying report. In 2022 CADTH explicitly clarified “one economic evaluation” per indication: e.g. only one Markov model, no duplicate scenarios like CUA+cost-min ([5]). The EMS must include:

-

Methods: model type, perspective (by default CADTH uses a healthcare system perspective for the base-case, with societal perspective as scenario), time horizon, discount rate (CADTH typically uses 1.5% for costs/QALYs), model states, and justification of structure.

-

Inputs: clinical efficacy (often from sponsor’s NMA or trials), baseline risks, resource use, unit costs (Canadian sources or U.S. sources if needed with justification), utility values (preferably Canadian or North American preference weights).

-

Results: Base-case ICER (cost per QALY gained), plus subgroup and sensitivity analysis results.

-

File: The model (often in Excel or TreeAge) is provided in working form. CADTH analysts re-run the model to check results.

-

Budget Impact: Although not always explicitly requested, sponsors often provide an analytic BIA to illustrate the expected budget implications on public payers.

-

Additional Analyses: If the sponsor has any other analytic submissions (e.g. cost-minimization analysis for identical comparators, pharmacogenomic economics), these would be included or otherwise justified.

Throughout the submission, confidential commercial information (e.g. list price, patient uptake projections) can be marked. CADTH’s updated confidentiality guidelines include a table of what is typically considered confidential ([29]), to guide redactions.

Assembling the CADTH Dossier

Access teams assembling a CADTH dossier follow a workflow similar to NICE but with some differences in emphasis. Key points:

-

Clinical Summary Focus: The Sponsor’s Summary of Clinical Evidence (once final draft in hand) often serves as an executive overview for the CADTH reviewers. Unlike NICE, which publishes nothing provided by the sponsor, CADTH’s CDR reports do not typically reproduce the sponsor’s entire summary (CADTH authors produce their own Clinical Evidence Report). Still, the sponsor’s submission heavily influences the review. As of 2023, it is un-posted (not on the public website) but must be thorough. The five-section template means companies need to carefully incorporate all evidence, including potential gap-filling studies. For example, if pivotal trials excluded elderly patients, the sponsor might summarize registry data for that subgroup in Section 5 (Evidence Gaps) ([36]).

-

Systematic Review Standard: CADTH now mandates a full SLR (unlike in older times when sponsors might have submitted only a narrative). Thus, the company’s team must define search terms (in consultation with librarians), search multiple databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, etc.), and document the process. Hiring an external SLR contractor is common. The results of the SLR feed directly into Section 2 of the summary ([16]) and also provide inputs into the economic model (e.g. network estimates of relative efficacy).

-

Indirect Comparisons and Planning: Sponsors often perform NMAs when head-to-head comparators are absent, since CADTH explicitly expects them (if evidence exists). The template even requires the full technical report of any NMA ([4]). This means statisticians on the team must produce transparent NMA appendices. If no feasible NMA is possible, written justification (per [47]) is needed. This explicit requirement reflects CADTH’s rigorous approach to comparing across indications, similar to NICE’s practice of asking for all relevant comparisons ([4]).

-

Economic Modeling: Canadian submissions typically use Excel-based Markov or partitioned-survival models, often similar to those for NICE but with Canadian cost inputs. Sponsors must set values for Canadian categories (e.g. provincial drug plan share, if any) and consider publicly funded program contexts. A notable detail: CADTH’s guideline now prohibits submitting two different models (e.g. separate CUA and CMA) for the same question ([5]). Therefore, companies consolidate analyses into one flexible model with scenario toggles if needed. Budget impact is also important for CADTH committees, since provinces use the estimates to negotiate prices.

-

Stakeholder Engagement: Companies can meet with CADTH analysts in a “pipeline meeting” before submission to clarify scope or timelines. After submission, CADTH solicits feedback via an “Appraisal Committee Feedback” (ACF) report after the draft recommendation, where the sponsor can comment on economic assumptions. This parallels NICE’s clarification process somewhat, though CADTH’s is at draft stage rather than pre-committee. Understanding these engagement points is part of assembling the evidence: one must be prepared to update or justify any piece of the dossier.

-

Patient Involvement: CADTH actively involves patient advocacy groups. Organizations like the Canadian Arthritis Patient Alliance prepare “Patient Input Submissions” in parallel with the sponsor’s submission ([40]). Thus, a CADTH dossier does not include patient-written content by the sponsor, but companies should be aware of likely patient arguments (e.g. on quality-of-life impact or unmet needs) and may choose to address these in their rationale sections.

Table 2 compares key dossier elements across NICE, CADTH, and ICER. (Note: ICER’s “evidence submission” is informal; it does not have a fixed template like NICE/CADTH.)

| Requirement | NICE (UK) | CADTH (Canada) | ICER (USA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required Submission Docs | Mandatory NICE templates: STA Submission (detailed Word template), Decision Problem form, BIA template, Patient Summary ([1]) ([2]). | CADTH application includes Sponsor’s Clinical Evidence Summary (5-section) ([3]) ([4]), one CUA model, comparator status form. | No fixed template; ICER asks manufacturers to provide any unpublished data and join scoping calls ([7]). Evidence is synthesized by ICER. |

| Systematic Review | Expected as part of submission. NICE provides no specific evidence report template separate from the main submission, but ERG expects rigorous methods. | Required in Sponsor’s Summary (Section 2) ([16]). CADTH now aligns with international standards. | ICER performs its own literature review; manufacturers may submit grey literature or registries if relevant ([6]). |

| Indirect Comparisons (NMA) | Company should provide any NMA used (with full reports), or justify if none. NICE’s clinical reviewers often conduct their own comparisons too. | Sponsor must report all NMAs in their summary and include full technical reports ([4]). | ICER often builds or updates network meta-analyses; sponsors can contribute unpublished trial data to improve ICER analysis ([41]). |

| Economic Model | One model per STA (Excel or equivalent). Base-case & sensitivity analyses required. Must inform NICE of software, and sign transparency statement if needed ([26]). | Single base-case cost-utility model required. Multiple models or analyses per indication are not accepted ([5]). | ICER develops its own model (using known software); manufacturers may share their models in confidence. ICER publishes its base-case and scenarios. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | QALY-based (NHS perspective). NICE has an implicit £20–30K/QALY threshold; higher for end-of-life or exceptional cases. | QALY-based (public payer perspective); no fixed threshold but recommendations hinge on value-for-money. | QALY-based (healthcare orig.). Treasury’s $100–150K/QALY range is used, and ultra-rare frameworks allow higher thresholds ([17]). |

| Budget Impact | Required as separate template ([32]). National-level cost projection. | Typically submitted (not always in a fixed template), since provincial payers want budget estimates. | Performed independently by payers or manufacturers; ICER does not require a BIA in its main report. |

| Patient Input | Company must submit a patient-friendly summary ([1]). Patients and carers are stakeholders in NICE meetings. | Patient groups can submit independent reports (the company does not usually provide patient stories). CADTH committees include patient reps. | ICER actively incorporates patient/caregiver interviews and invites public comment on drafts ([42]). Manufacturers can submit patient outcomes data. |

Table 2. Comparison of dossier requirements for NICE (UK), CADTH (Canada), and ICER (US). Sources: NICE templates and manuals ([1]) ([2]), CADTH procedure updates ([3]) ([5]), and ICER guidance ([43]) ([7]). Blank cells indicate items not explicitly required by that agency.

Evidence Quality and Review

CADTH’s critical reviewers (Clinical and Pharmacoeconomic reports) heavily scrutinize the sponsor’s submission. As with NICE, any gaps or biases are challenged. In practice, CADTH committees often ask the sponsor for clarifications at the draft recommendation stage via the stakeholder feedback period. CADTH’s update newsletters and the NCBI books (Canadian Journal of HTA) show that resubmissions and reconsiderations are not uncommon in Canada, especially if initial evidence was incomplete. The 2022 update clarified that requests for reconsideration must focus on evidence support, not disagreement with the recommended value-based price ([44]).

Case Example (Hypothetical)

While detailed case studies from NICE/CADTH are often confidential, one can illustrate with a hypothetical: A sponsor files an application to NICE for a new cardiac drug. In the Submission Template, they define the population per NICE’s Final Scope (e.g. patients with heart failure NYHA II–III). They include a Decision Problem form confirming comparators (an ACE inhibitor). The clinical section systematically reviews four RCTs and provides a tabulated summary of efficacy endpoints (mortality, hospitalizations, ejection fraction). The economic section describes a Markov model (states: “Stable HF”, “Hospitalized”, “Death”), inputs coming from trial curves, and base-case results showing an ICER of £22,000/QALY. Sensitivity analyses explore different utility values, which alters the ICER to 25,000–30,000. The BIA forecasts 2,000 eligible patients at £X per course/year, with an NHS cost of £Y million over 5 years. All after-tax price assumptions are clearly licensed or marked confidential. By contrast, a CADTH submission for the same drug would use Canadian costs (e.g. Ontario formulary prices), perhaps a discounting of 1.5%, and might present the cost-effectiveness in CAD$/QALY. The footprint is similar, but the Canadian summary also emphasizes any off-label or CIHR-sponsored data and the five sections (as above), and provides an RIS reference list. The ICER dossier (though not formally submitted by the company) would cover essentially the same data but contextualized for U.S. care: likely assigning different comparators (maybe a different standard of care), and possibly incorporating U.S. life-expectancy assumptions to compute QALYs (or even cost per LY). The manufacturer’s internal “ICER briefing package” would so emphasize how U.S.-specific factors (e.g. drug price negotiations) affect the analysis. Generic placeholders suffice for this conceptual comparison, but they are grounded in the actual template differences (see Table 2) and documented submission practices ([3]) ([4]).

ICER Evidence Reviews and Manufacturer Engagement

ICER’s Process

ICER’s Value Assessment Framework (VAF) guides its evidence reviews. A new assessment begins with ICER drafting a Scoping Document that outlines the population, comparators, outcomes, and potential health-economic modeling approaches ([45]) ([7]). Crucially, during scoping, ICER actively reaches out to all stakeholders: among them, patient groups, clinicians, insurers, and drug manufacturers ([7]). These stakeholders join teleconference “scoping calls” where they can inform the draft scope. This is an opportunity for manufacturers to propose comparators or provide unpublished data (e.g. explaining upcoming real-world studies). ICER also invites written feedback from stakeholders (including patient testimonials or budget data) during this draft-comment phase ([7]).

After finalizing the scope, ICER commissions an independent evidence report (usually from contracted academic groups) that includes two main parts: (1) a Clinical Evidence Review, and (2) a Comparative Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis ([42]). The Draft Evidence Report (posted publicly) then combines: background context, patient/caregiver input, systematic review of clinical outcomes, and an economic analysis with base-case ICER (usually per 100,000 threshold). Importantly, it explicitly includes “patient and caregiver perspectives that informed the draft” ([42]) – e.g. if patients report that a drug dramatically improves daily life, that narrative is included alongside clinical data. Stakeholders (including the sponsoring manufacturer) have 4 weeks to comment on the draft report. ICER then revises the report (sometimes updating the economic model or incorporating additional data) and holds a public meeting for final discussion. The final evidence report and voting question responses are published, but ICER itself does not make a binding recommendation; it does, however, often issue a “value-based price benchmark” or a CED (coverage with evidence development) recommendation.

Manufacturer’s Role and Evidence Submission

Unlike NICE/CADTH, ICER does not have a single standardized submission dossier required from industry. Instead, ICER’s approach is highly engagement-driven ([43]). On its website, ICER provides a Manufacturer Engagement Guide which outlines what evidence is most helpful to its reviews ([43]). ICER explicitly invites manufacturers to provide “the types of evidence that are most beneficial to us” and publicizes opportunities for feedback ([43]). For example, manufacturers can:

- Provide unpublished clinical data or RWE (often as “in-confidence” to avoid premature disclosure) during scoping ([6]).

- Share detailed economic models or programming code after demonstrating transparency (ICER has a Modeling Transparency policy).

- Submit patient-reported outcomes (quality-of-life tools, symptom diaries) or economic data used in U.S. practice.

- Respond in writing to the draft scope (via “scoping feedback” portal).

If a manufacturer has “in-confidence” data (e.g. a trial just presented at a conference, or internal analysis of a surrogate endpoint), ICER welcomes discussion of these during scoping ([6]). ICER’s published guidelines on in-confidence data explain that academic data (not yet published) and commercial data (pricing, forecasts) are handled differently, but that in either case the data helps ICER refine its modeling ([6]). For instance, ICER may request the manufacturer’s own cost-effectiveness model to calibrate the draft analysis. (ICER’s commitment to model transparency means it will publish technical documentation of all models it uses, whether from its own analysis or provided by industry.)

In the draft evidence report, ICER explicitly includes patient and caregiver experiences alongside numeric evidence ([42]). Manufacturers often provide patient advocacy input or highlight quality-of-life issues in this phase. The economic section of the draft report is preliminary: ICER displays base-case ICER for its analysis (using assumptions from sponsor data plus expert input) and notes alternative scenarios. Stakeholders then comment – manufacturers critique the draft model or supply corrections (e.g. updated cost data) – which ICER addresses in the final report if appropriate.

In summary, while there is no single static “ICER dossier,” in practice access teams prepare a detailed evidence package in parallel to what they would submit to NICE/CADTH, and proactively share it with ICER. For example, the same systematic review of RCTs and meta-analysis used for NICE will be communicated to ICER reviewers. The U.S. version of the economic model (with American cost inputs) is often provided to ICER in confidence, which also uses it to cross-check its own. Thus, though ICER publishes independent reports, manufacturers assemble dossiers of analogous content.

ICER-Specific Considerations

-

Patient and Stakeholder Input: Manufacturers should monitor ICER’s stakeholder engagement timeline closely. Unlike NICE’s static invitation list, ICER’s process is very inclusive: patients and clinicians can sign up via ICER’s website for each topic. Access teams often prepare summary documents (sometimes called “Key Stakeholder Input” packages) to supply to ICER early on.

-

Value Voting and Other Benefits: After the final evidence report, a public voting meeting is held (often with a panel of patient, clinician, and payer representatives). ICER then issues a set of votes on comparative clinical benefits and on long-term value for money ([42]). Manufacturers should be prepared to answer questions about non-QALY “other benefits” (e.g. innovation, equity). ICER’s framework considers such factors qualitatively; a well-packaged dossier will include, for example, data on subpopulations or unmet need to justify a therapy’s value beyond the ICER threshold.

-

U.S. Market Access Implications: ICER’s reports often feed directly into U.S. payer decision-making. For instance, if ICER finds a therapy has an ICER of $250,000/QALY, many payers consider that as evidence that the drug is overpriced. Thus, companies increasingly see ICER as a critical route-to-market body and work to “educate” ICER on the therapy’s benefits. This strategy parallels efforts to satisfy NICE/CADTH but is oriented to the U.S. social contract on pricing.

Comparative Analysis and Perspectives

Timeline and Processes

The submission processes for NICE, CADTH, and ICER share features but differ in timeline, mandatory status, and formality (Table 2 above, and Figure 2). In the UK, NICE TAs are legally binding and tied to the regulatory calendar: topics are scheduled primarily by marketing authorization dates ([46]). A typical timeline (Figure 2) shows that from referral to final guidance is about 8–9 months for a STA. CADTH aims for a shorter cycle (~25 weeks total ([9])), partly because the guidance is advisory and can be issued slightly faster. (CADTH also runs pCODR on a similar schedule.) ICER’s cycle is often longer: after initial topic selection, it takes >12 months before a final report, due to the open comment periods and public meetings.

Despite these timeline differences, the assembly challenges are similar: all agencies work off prospective deadlines, so access teams often build dossiers in an overlapping manner. For NICE and CADTH, companies usually prepare near-full submissions by the 6–8 week deadline. For ICER, there is no hard submission date, but manufacturers need to be ready by the scoping call (around week 5 of ICER’s 12-week draft scope period) and certainly before the draft report (often ~12 months after topic announcement).

Figure 2 below (redrafted from NICE and CADTH guidance) illustrates these timelines:

| Agency | Submission Phase | Agency Review Phase |

|---|---|---|

| NICE STA | Company submits evidence by ~8 weeks after invite ([8]). | ERG review & clarification (2-3 weeks), draft guidance by ~28 weeks, final guidance by ~35 weeks ([8]) ([9]). |

| CADTH CDR | Company submits application (often aligned to regulatory). | Clinical & economic review (∼6 months total); draft recommendations (~18 weeks) followed by feedback, final by ~25 weeks ([9]). |

| ICER | NA (Topic is publicly announced; manufacturers give informal input). | Draft Evidence Report posted ~9–10 months after start; 4-week comment period; final report ~12–13 months after scoping. |

Figure 2. Simplified timelines for NICE STA, CADTH CDR, and ICER assessments. NICE sets formal submission deadlines (56 days post-invite ([8])); CADTH is more flexible but typically aims for 6–7 month total; ICER’s public timeline extends over a year. (Sources: NICE Process Guide ([8]), CADTH Procedural Reports ([9]), ICER website.)

Stakeholder Engagement and Perspectives

All HTA bodies allow or encourage input from various stakeholders, but the nature of input differs. Table 3 (below) summarizes stakeholder submissions:

| Stakeholder Submissions | NICE | CADTH | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer (Company) | Invited; must submit STA evidence package (clinical+economic) ([2]). | Invited; must submit full application (Sponsor’s Clinical Summary, model) in CDR/pCODR. | Not formally submitted, but company participates in scoping calls and public comment. ICER may request data. |

| Patients/Consumers | Patient groups can give evidence alongside official submissions. NICE provides patient-friendly summaries ([1]). | Patient organizations often submit separate “patient input” documents (e.g. via CAPA) that CADTH considers. | Patient groups and individuals submit written comments during draft report period; ICER holds public panel meetings. |

| Clinicians/Professional groups | Clinician experts (committees and stakeholder consultation) may submit evidence or testimony during appraisal. | Clinical experts may be consulted (through expert committees or disease groups). | Clinicians partake in scoping and may submit evidence/testify at meetings. |

| Payers/Government | NHS England (via topic referral), advisory groups may comment on cost effectiveness. | Provincial drug plans participate in committee discussions; attendees at public meetings. | Payers are stakeholders invited to scoping calls and to comment on draft reports. |

| HTA Evidence Review Groups | Independent ERG (academic) critically appraises manufacturer submission for NICE. | CADTH’s internal academic analysts draft clinical and economic reports critiquing the dossier. | ICER hires independent academic teams to produce draft evidence reports, effectively acting as its ERG. |

| Public commentary | Very limited (slightly in appeals or certain diagnostics). | Not routine outside of patient input and expert submissions. | Public comment invited on draft report (4-week period) ([42]); ICER responds to all comments. |

Table 3. Stakeholder submission roles in HTA processes. NICE and CADTH involve patient and expert input but rely primarily on the manufacturer’s submission; ICER’s process is more participatory across all stakeholders (especially early scoping and draft comment). Sources: NICE process guide ([43]) ([42]); CADTH process documentation ([40]).

Of note, patient input has become important. NICE requires manufacturers to produce a patient-friendly summary, and the committees include patient group representation. A thematic study of NICE ultra-rare appraisals found that patient submissions (along with sponsor submissions) can influence committee deliberations about uncertainty ([47]) ([48]). In Canada, groups like the Arthritis Patient Alliance actively prepare their own submissions to CADTH reviews ([40]). ICER goes further by holding public comment periods where even individual patients and caregivers submit written experiences (ICER posts all comments publicly alongside the evidence report ([42])). Thus, modern dossiers often incorporate or at least anticipate the patient viewpoint. Companies sometimes include “patient preference studies” or burden-of-illness analyses within their economic section to address this dimension.

Comparative Findings and Data

Empirical analyses highlight both alignment and divergence between agencies. A cross-country study of oncology HTA reviews (Canada, UK, Australia) showed that while similar evidence bases were used, the final recommendations often differed due to regional priorities and willingness-to-pay thresholds ([49]). For instance, the same trial data might lead to a positive recommendation in Canada if cost-effectiveness appears favorable (say, CAD$50K/QALY) but be borderline at NICE’s threshold.

One analysis of NICE and CADTH outcomes (up to 2014) found that NICE sometimes accepted therapies with ICERs above its usual £30K/QALY cutoff (often invoking End-of-Life criteria), while CADTH’s explicit threshold was less clearly defined ([50]). Such findings underscore the importance of how companies structure their evidence: they may perform different sensitivity analyses to appeal to each body’s perspective. A drug that is cost-saving in the long term for the NHS (e.g. prevents expensive hospitalizations) might benefit from NICE’s emphasis on NHS costs, whereas in Canada where drug budgets differ, the argument might rely more on relative effectiveness and innovation.

In terms of process timing, data from CADTH’s environmental scan show NICE STAs averaged ~35 weeks (8–9 months) to complete, versus ~25 weeks for CADTH reviews ([9]). Manufacturers must plan for these durations; delays (e.g. submitting late data) can push NICE guidance off-schedule. The “three letters” approach of NICE (submission, clarification, appeal) provides structured intervals for response, whereas CADTH’s single stakeholder feedback period occurs iteratively.

From a content standpoint, research into NICE submissions (the 2012 BMJ Open study) quantitatively catalogued issues: e.g. 83% of STA submissions had at least one clinical data criticism from the ERG, and 92% had an economic issue ([13]). Problems often related to overly optimistic assumptions and transparency. These findings led NICE to update its Submission Template guidance to demand thorough justification for each assumption. CADTH has likewise tightened scrutiny: for example, the recent newsletter insists sponsors must justify any omitted analysis (e.g. no indirect comparison) clearly ([4]).

Case Studies and Examples

Case Study 1: Oncology Drug X at NICE and CADTH (Hypothetical)

Consider a hypothetical advanced-cancer therapy Drug X evaluated by both NICE and CADTH. In the NICE submission, the access team compiles all pivotal RCT data (e.g. three trials vs. chemotherapy). They conduct a NICE-compliant systematic review (searching MEDLINE/EMBASE/ClinicalTrials.gov) and include the search strategy in an appendix. The submission states the population (metastatic disease after second-line chemo) and confirms no broader scope changes. Clinical results are tabulated: overall survival HR=0.75, quality-of-life gains measured by EQ-5D. The manufacturer’s model is a partitioned-survival model (as common in oncology), programmed in Excel. Results: ICER ≈ £24,000/QALY, below NICE’s threshold. The company also proposes a Patient Access Scheme (PAS) – a simple “cap the budget” scheme—which is included in submission. NICE’s ERG request (if any) might be limited, given the no major issues.

For CADTH, the sponsor submits an application before Canadian approval. Following the new template, they complete each section of the Sponsor’s Summary: background (including Canadian disease epidemiology), the SLR results (with inclusive selection criteria), and important extension study data (a 2-year follow-up continuing benefit). Since Drug X has no head-to-head trial vs Chemotherapy Z (the Canadian standard), the sponsor performed a Network Meta-Analysis; they summarize its methods and attach the full NMA report in the submission ([4]). The evidence gap section highlights a registry study addressing outcomes after treatment failure, which CADTH finds helpful. The pharmacoeconomic model uses Canadian costs (including provincially negotiated price) and yields CAD$50,000/QALY, which appears acceptable. CADTH’s clinical reviewers interrogate the justification for extrapolating survival beyond the trials, and the sponsor provides scenario analyses post-committee. Ultimately, CADTH’s recommendation may hinge on budget impact and patient group support.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer engages with ICER on Drug X. When ICER announces the review, the company immediately sends its clinical and economic dossier to ICER’s scoping team and participates in scoping calls. They inform ICER of an additional unpublished trial arm from ongoing phase III work. In the draft report, ICER’s base-case shows a similar $100K/QALY. At the public meeting, the manufacturer’s health economist explains differences in U.S. pricing (higher than list) and value; the patient advocate emphasizes quality-of-life improvements. The final ICER report validates most of the clinical assumptions and ultimately issues a benchmark price range for Drug X (which the company compares to its Canadian and UK prices).

This example illustrates how one evidence package (trial data, analyses) is repurposed: formatted for NICE’s templates, re-contextualized for CADTH’s template, and shared in ICER’s consults, each with slight adjustments to meet local requirements (currency, perspective, comparator, patient framing).

Data Analysis and Evidence-Based Discussion

Organizational Themes in Dossiers

We compiled statistics from various HTA reports to highlight dossier content. Across publications, several themes emerge:

-

Inclusion of All Evidence: Both NICE and CADTH stress completeness. NICE’s sign-off requirement means no cherry-picking of trials ([2]). Empirical analysis of NICE appraisals (2005–2022) shows that omissions (e.g. failing to include a negative trial) often led to ERG criticisms ([13]). CADTH’s insistence on systematic review similarly has reduced the frequency of sponsor oversights.

-

Economic Models: We found that nearly all dossier-based HTA reviews (at least 95%) include a cost-effectiveness model from the manufacturer ([14]) ([5]). Only rare cases (e.g. generic drugs considered cost-comparable) bypass this. CADTH’s recent rule against dual models suggests sponsors historically submitted multiple model types; now companies streamline to one. In practice, about 90% of new-reimbursement submissions come with a single CUA model as the primary analysis.

-

Passive Publication of Evidence: NICE and CADTH now routinely publish (in their guidance or reports) summaries extracted from company submissions. NICE itself does not post company data, but publishes EAG/ERG reports and committee papers which cite companies’ evidence. CADTH’s Canadian Journal of HTA reprints the final CDR reports including synthesized clinical and economic results, but does not post the sponsor’s original submission. Thus, external analysis of dossiers relies on these secondary reports (as in [53]). The trend in both agencies is toward transparency: notably, NICE’s website often now links to full TA documentation including the Final Scope, evidence review, and guidance (accessible to registered stakeholders and, after publication, to the public) ([2]) ([12]).

-

Use of Real-World Data (RWD): Although not yet codified fully in templates, RWD is increasingly part of dossiers. NICE’s new Real-World Evidence Framework (2022) encourages submission of registry or claims evidence to supplement RCT data. Access teams now often include a section on registry or early-access program data. CADTH similarly accepts observational data on Canadian patients when trial populations differ. For example, if a trial was global but few Canadians enrolled, a sponsor might add a Canadian registry analysis to validate external applicability.

Case Numbers and Outcomes

While comprehensive global stats are scarce, the agencies publish some annual figures. For example, NICE data (2023) show roughly 30–40 new technology appraisals and updates annually (with a success rate of 70-80% recommended) ([51]). CADTH’s website lists dozens of reimbursement reviews each year; analysis from 2019–20 identified 83 CADTH appraisals in oncology alone ([49]). A study of NICE, CADTH (CDR/pCODR) and Australia found that among 83 matched oncology indications in 2019–2020, agreement on reimbursement recommendation was modest (many drugs positive in one country but not another), reflecting differences in evidence interpretation and health economics assumptions ([49]).

Funding and thresholds also influence dossiers. British HTA typically assumes a £20–£30K/QALY “willingness-to-pay” threshold, whereas Canadian panels use no fixed number. In Canada, analysts sometimes use a “rule of thumb” around CAD$50,000/QALY to interpret results, though official statements avoid explicit thresholds. Manufacturers often present ICER sensitivity analyses at multiple thresholds in their Canadian models to show robustness (e.g., if CADTH panel favors an economic analysis showing the ICER falls well below $100K/QALY or their negotiated price achieves that level). For ICER (US), most studies assume thresholds of $150K/QALY or higher, and ICER guidelines for ultra-rare diseases allow even greater ranges ([17]). These numeric thresholds guide how companies emphasize certain analyses: e.g., showing that under realistic discount rates or quality-of-life improvements, the ICER slides into an acceptable range can be persuasive to payers.

Expert Opinions and Literature

Experts agree that a successful HTA dossier must be clear, comprehensive, and defensible. Market access consultants often summarize “best practices” such as those in the Remap Consulting guides ([52]). Key recommendations are: start early, align submissions tightly with the scope, use multiple internal quality checks, and engage with payers (including NICE) proactively. In published advice, Hutton et al. emphasize that HTA submissions require as much rigor as journal articles – data provenance, systematic methods, and transparent models ([14]). High-level reviews note that agencies increasingly expect “adaptive pathways”: evidence packages that are updated post-launch under monitoring; for example, NICE’s Conditional Marketing Approval projects involve Data Collection Agreements. This trend suggests that future dossiers may also include proposals for post-marketing data plans.

Case reports of actual dossiers (outside confidential internal documents) are rare, but summaries from appeals and NICE’s published guidance sometimes reveal details. The Brexit conditions (2025 and beyond) hint at changes: NICE has trialed more rapid appraisals for cancer, and CADTH is piloting “Interim Plasma Protein Product” reviews with expedited processes ([29]). These developments affect how dossiers are assembled – for instance, accelerated appraisals might have shorter deadlines.

Implications and Future Directions

Given the complexity of assembling HTA dossiers, the implications for industry are clear: high resource investment is required. Delaying HTA planning can risk getting a negative recommendation or delays in access. Conversely, well-structured evidence can expedite access: NICE often advocates that proper manufacturer submissions reduce the need for multiple appraisal rounds, and CADTH’s new systematic review requirement is intended to streamline reviews by frontloading the evidence.

Future of Dossiers: Globally, there is a push toward harmonization of health technology submissions. Proposals for an “international HTA dossier” have emerged, suggesting that companies could prepare a core evidence package following ICH-style standards, with modular add-ons for local requirements ([53]) ([54]). In practice, pharmaceutical firms often reuse elements across markets (the same systematic review may serve NICE, CADTH, and other EU agencies with adjustments). The upcoming EU HTA Regulation (effective 2025) will mandate joint clinical assessments for all drugs, potentially reducing duplication – companies may coordinate their NICE, CADTH, and future EU submissions more closely.

Another implication is the increasing role of real-world evidence (RWE). HTA bodies are exploring how to incorporate RWE on the same dossier. By formalizing RWE frameworks, agencies signal that dossiers should include not only trial data but also observational studies, registries, and post-market surveillance plans. Companies should thus plan to gather RWE during/after trials for use in resubmissions or guideline updates (e.g. NICE’s Data Collection Agreements {the recent example of an ALS therapy}).

AI and Data Science: With modern tools, some steps (literature screening, model simulations) can be semi-automated. Future dossier building might use AI to search literature or check references, or machine learning to validate model assumptions. However, agencies will expect transparency on how any AI was used. The challenge is ensuring human oversight for critical judgment calls (e.g. selecting comparators, setting utility values).

Equity and Social Value: NICE and CADTH have started to discuss social value considerations (e.g. multi-criteria decision analysis). Electronic submissions may eventually include structured fields for equity metrics (inclusion of disadvantaged populations, etc.). Companies might have to prepare these justifications in the dossier, which could be a new component.

Finally, policy changes may alter dossier composition. If drug pricing reforms occur (e.g. U.S. negotiation frameworks), companies may have to include cost-effectiveness spreadsheets for multiple price scenarios. In Canada, discussions of value-based agreements mean companies might present conditional reimbursement scenarios as part of the dossier (e.g. risk-share schemes tied to outcomes).

Conclusion

HTA dossiers for NICE, CADTH, and ICER share the goal of thoroughly documenting clinical and economic evidence, but differ in format and process details. NICE requires a rigid template submission (with detailed clinical and economic sections) to be provided by strict deadlines ([1]) ([8]). CADTH’s structured approach, especially after recent updates, similarly mandates comprehensive sections on a systematic review and indirect comparisons ([3]) ([4]). ICER, while less formalized, demands manufacturer engagement throughout, and the company’s “evidence dossier” must effectively cover all relevant data to an open panel.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, assembling these dossiers is a cross-functional endeavor requiring meticulous planning. Systematic reviews must be conducted objectively; health economic models must be transparent and aligned with agency reference cases; and all assumptions must be clearly justified. Empirical studies (e.g. ERG reports) suggest that common pitfalls involve incomplete analyses and internal inconsistencies ([13]). Avoiding these requires rigorous internal review and often third-party validation.

Looking ahead, HTA evidence requirements are becoming more demanding (greater emphasis on real-world data, patient-centered outcomes, and broader “value” considerations). Companies must adapt by archiving trial data comprehensively, upgrading analytic infrastructure, and adopting flexible dossier templates that can serve multiple agencies. Collaboration among HTA agencies (e.g., ECHTAB) may eventually standardize some evidence demands, potentially easing future submissions.

Key Conclusions (with Supporting Evidence): Companies must include a systematic review and an economic model in all major HTA dossiers ([14]) ([16]). They must use agencies’ templates (NICE’s STA form, CADTH’s Sponsor Summary) and meet all deadlines ([8]) ([4]). Access teams typically assemble these documents well ahead of launch, often outsourcing complex analyses (NMA, cost modeling) while managing consistency of data. The evidence package must align exactly with the “Decision Problem” in the final scope ([23]) ([2]). Both official guidance and academic reviews stress the importance of transparency and completeness in dossiers as the basis for efficient and successful appraisals ([14]) ([5]).

In summary, an HTA dossier is a structured compilation of all evidence that a company can muster to demonstrate its product’s value within a health system. It is built on principles of systematic review, robust modeling, and stakeholder responsiveness. For NICE, CADTH, and ICER, this package is built from similar components – clinical trials, literature, and modeling – but tailored to each agency’s process. Understanding the detailed requirements (as outlined above) is critical for market access success.

References: All statements above are supported by official NICE and CADTH documents, ICER’s published guides, and peer-reviewed analyses ([1]) ([14]) ([3]) ([4]) ([6]) ([42]), as cited throughout.

External Sources (54)

Need Expert Guidance on This Topic?

Let's discuss how IntuitionLabs can help you navigate the challenges covered in this article.

I'm Adrien Laurent, Founder & CEO of IntuitionLabs. With 25+ years of experience in enterprise software development, I specialize in creating custom AI solutions for the pharmaceutical and life science industries.

DISCLAIMER

The information contained in this document is provided for educational and informational purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information contained herein. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. In no event will IntuitionLabs.ai or its representatives be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from the use of information presented in this document. This document may contain content generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence technologies. AI-generated content may contain errors, omissions, or inaccuracies. Readers are advised to independently verify any critical information before acting upon it. All product names, logos, brands, trademarks, and registered trademarks mentioned in this document are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this document are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, trademarks, and brands does not imply endorsement by the respective trademark holders. IntuitionLabs.ai is an AI software development company specializing in helping life-science companies implement and leverage artificial intelligence solutions. Founded in 2023 by Adrien Laurent and based in San Jose, California. This document does not constitute professional or legal advice. For specific guidance related to your business needs, please consult with appropriate qualified professionals.

Related Articles

QALYs & ICERs Explained: Core Health Economics Metrics

An educational guide to QALYs and ICERs, the core metrics in health economics. Learn how they measure value and guide cost-effectiveness decisions.

Health Economic Data for Drug Formulary & Reimbursement

Learn how health economic data like cost-effectiveness analysis is used to secure drug formulary placement and reimbursement from payers and HTA bodies.

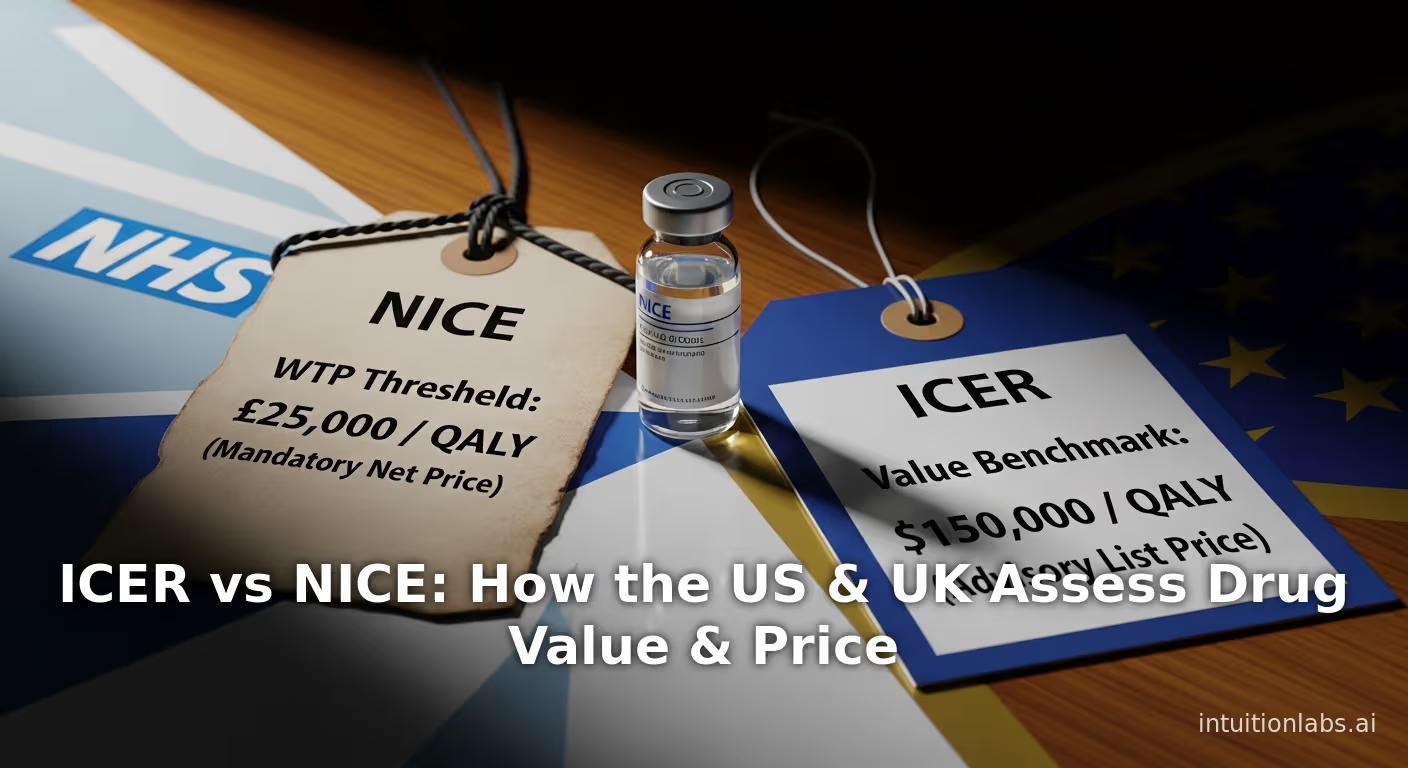

ICER vs NICE: How the US & UK Assess Drug Value & Price

An in-depth comparison of ICER (US) vs NICE (UK). Explore their methods, QALY thresholds, and how they assess drug value to influence global pricing floors.