QALYs & Quality of Life: Justifying Specialty Drug Costs

Executive Summary

High-cost “specialty” drugs (e.g. biologics, orphan and gene therapies) are often priced tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient-year. In justifying these prices, manufacturers and payers increasingly rely on measures of patient quality of life (QoL) – subjective patient-reported outcomes (PROs) quantified into indexes (e.g. Quality-Adjusted Life Years, QALYs) – to demonstrate added value. 1p>\ Subjective data from patients (symptom severity, functional status, well-being) are collected via validated QoL instruments (e.g. SF-36, EQ-5D, disease-specific scales) and converted to numeric utility scores. These utilities are then incorporated into cost-effectiveness analyses: for example, gaining 0.1 QALY with a new drug may justify thousands of dollars in extra cost compared to standard care. In practice, health technology assessment bodies (e.g. NICE in the UK) and pricing/reimbursement decision frameworks (e.g. ASCO framework, ICER reports) scrutinize whether a drug’s incremental cost per QALY falls within an acceptable range (traditionally ~£20–30k/QALY in the UK or up to ~$100k/QALY in the US) ([1]) ([2]). 1p>\ Proponents argue that well-designed QoL measures capture patient priorities (pain relief, independence, psychosocial impact) beyond clinical endpoints, and can justify high launch prices when large overall health gains are demonstrated. For example, clinical reviews have shown that 100% of studies using a breast-cancer QoL questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) reported significant functional improvements with new specialty agents, at median cost-effectiveness ~$52k per QALY ([1]) ([3]). Similarly, patient demand studies find individuals assign very high value to life-extending specialty treatments: one analysis found the aggregate “willingness-to-pay” for expensive oncology drugs was about 4 times their actual cost ([4]). 1p>\ Critics respond that subjective QoL data is inherently variable and can be manipulated. Test-retest reliability of subjective well-being measures is only moderate (often 0.50–0.70) ([5]), much lower than objective measures. Response shifts (patients’ changing internal standards) and placebo effects can confound interpretations. Disability rights groups also note that QALY methods may implicitly devalue chronically ill or disabled lives. Moreover, real-world evidence often shows that early-trial QALY gains shrink in broad patient populations. Nonetheless, regulatory and HTA guidelines generally accept PROs when rigorously validated ([6]). Reports by ASCO and NICE emphasize that quality-of-life should be a core endpoint alongside survival, even if it has not always been measured consistently in trials ([7]) ([8]). 1p>\ This report presents an in-depth analysis of how subjective QoL data are quantified (scoring instruments, utility derivation, modeling) and used to justify high-cost drugs. We cover the history of QoL assessment, current methodologies (including psychometric standards for PRO instruments), payer frameworks (cost-per-QALY thresholds, patient-reported “willingness to pay”), diverse stakeholder perspectives (patient, manufacturer, payer, ethicist), and detailed case studies (e.g. gene therapies, cystic fibrosis modulators, oncology biologics). Data from published studies and HTA reviews are synthesized in tables and figures to illustrate key points. Our evidence-based conclusions highlight both the power and pitfalls of converting subjective patient experience into economic value, and discuss emerging trends (digital PRO collection, personalized valuation) that will shape future specialty drug decisions.

Introduction and Background

Specialty Drugs and the Value Debate. Specialty pharmaceuticals – biotechnological, cell and gene therapies, and other novel agents – represent a rapidly growing share of healthcare costs. These drugs often target rare or complex conditions (e.g. rare genetic diseases, advanced cancers, autoimmune or neurologic disorders) and can extend or dramatically improve patients’ lives. However, R&D and delivery complexities make their prices very high: average specialty drug costs can be an order of magnitude above traditional small-molecule drugs ([9]). As public and private payers grapple with affordability, there is intense scrutiny of whether such prices are “worth it.” Increasingly, cost-effectiveness and “value-based” frameworks link price to the measured benefit, notably health-related quality of life. 1p>\ The concept of quality of life (QoL) in medicine refers to the patient’s subjective well-being and functional status in relation to health. It encompasses physical, psychological, social, and sometimes financial domains. Unlike purely clinical outcomes (tumor shrinkage, lab results), QoL assesses how a patient feels and functions day-to-day. The World Health Organization defines quality of life as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in context of culture and value systems… in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (WHO QoL Group) ([10]). In pharma, particularly for life-threatening or chronic diseases, QoL is often presented as a key outcome: a therapy that relieves severe symptoms or disabilities can be life-changing even if it does not dramatically extend survival. 1p>\ However, subjective data (“how does the patient feel?”) pose challenges. Different patients might report differently under similar conditions; psychological adaptation (patients adjusting expectations after disease onset) can alter their responses; and responses can be affected by questionnaire design or timing. Despite these concerns, structured QoL measurement has been standardized through patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments. These include generic tools (e.g. SF-36, EQ-5D) and disease-specific surveys (e.g. EORTC QLQ-C30 for cancer, CFQ-R for cystic fibrosis). Rigorous psychometric validation (ensuring reliability, validity, responsiveness) underpins their acceptance ([11]) ([12]). 1p>\ In health economics, subjective QoL data are often summarized as a health utility – a number between 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health) – in order to compute Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). A QALY represents one year of life weighted by QoL. For example, 0.5 QALY could represent one year at 50% health or 6 months at full health. QALYs allow comparison across conditions: a cancer drug that yields 1 extra year at 0.8 utility (0.8 QALY) might justify more cost than one giving only 0.1 QALY. The willingness-to-pay per QALY gained is a common threshold for judging cost-effectiveness. In practice, many health systems view ~$50,000–100,000 per QALY as a “good value,” with stricter limits (≈£20–30K/QALY) in systems like the UK’s National Health Service ([13]) ([2]). Thus, to “justify” a $100,000 specialty drug, the manufacturer must argue it produces correspondingly large health improvements – often measured in QALYs derived from patient QoL data. 1p>\ This interplay has become explicit in policy. The U.S. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) and similar bodies routinely assess new high-cost drugs via cost-per-QALY models. The FDA’s 2009 guidance on PROs shows regulatory interest in formally integrating patient QoL into labeling claims ([6]).Patient advocacy coalitions urge that QoL gains be factored into pricing so that patients truly benefit from costly therapies. Conversely, critics (including ethicists and disability rights groups) argue QALY-driven pricing is inherently biased – effectively “rationing” care by quality of life. Indeed, recent commentaries warn that QALY methodologies risk devaluing disabled patients unless adjusted ([7]). 1p>\ In summary, subjective patient data (QoL) have moved from anecdotal importance to a quantifiable pillar of drug valuation. This report examines how exactly such data are turned into justifications for high-cost specialty drugs. We provide historical context on QoL metrics, detail current measurement and analysis methods, survey stakeholder perspectives (patients, payers, industry, regulators), and analyze real-world examples of costly drugs whose value propositions hinge on patient-reported QoL improvements.

Measuring Subjective Quality of Life: Instruments and Psychometrics

To use QoL data in economic models, we must first understand how subjective patient experiences are quantified. Quality-of-life instruments are usually questionnaires standardized by experts and tested in clinical studies. They can be generic or disease-specific. Generic instruments (like the SF-36, EQ-5D, or Health Utilities Index) apply across a variety of conditions. Disease-specific tools (e.g. the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised (CFQ-R), EORTC QLQ-C30 for oncology, Diabetes Quality of Life measure, etc.) target particular patient populations and may capture domains more relevant to that disease. 1p>\ Generic Measures:

- SF-36 (Short-Form 36): A widely used generic health survey with 36 items covering 8 domains: physical functioning, role limitations (physical), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations (emotional), and mental health ([12]). Scores (0–100) are aggregated into two summary scores (Physical Component and Mental Component), where higher is better. SF-36 has been validated in “a wide variety of age, race, and disease populations” (including sickle cell, cancer, etc.) ([12]), and can gauge overall health status. Its companion preference-based index (SF-6D) maps SF-36 responses to a single utility score for QALY calculations.

- EQ-5D: A short generic QoL measure used in many economic evaluations. It asks patients to rate 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression), each at 3 or 5 levels of severity. The five responses form a health state (e.g. "no problems walking, some pain, etc.") which is converted into a utility (0–1) by applying a standardized value set (usually based on general population preferences). For example, a UK EQ-5D index yields typical utilities like 0.8 for mild disease. While not explicitly cited here, EQ-5D is universally employed in HTA bodies (NICE, ICER) and in published trials. It was noted by CADTH analysts that the EQ-5D’s measurement properties had not been fully assessed in every disease (e.g. cystic fibrosis), but it remains a “generic, preference-based HRQoL” instrument used for economic modeling ([14]).

- Health Utilities Index (HUI), 15D, etc.: Other generic utility measures exist, though less pervasive. They operate on similar principles (multi-dimension health states converted to utilities).

Disease-Specific Measures:

- EORTC QLQ-C30: A 30-item questionnaire developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, to assess QoL in cancer patients. It includes functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, social) and symptom scales (fatigue, pain, nausea, etc.), plus global health/QoL items ([15]). Scores are linearly transformed 0–100; higher on functional scales means better QoL, while higher on symptom scales means worse symptoms. Many oncology trials incorporate QLQ-C30 as an endpoint. For example, in a systematic review of specialty drugs for breast cancer, all studies reporting QLQ-C30 outcomes found significant improvements ([16]), underscoring that effective new cancer therapies often translate into better patient-perceived function.

- Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised (CFQ-R): A disease-specific QoL instrument for cystic fibrosis (CF) ([17]). It has versions for children, parents, and adults, covering domains like respiratory symptoms, digestion, emotional function, and treatment burden. Each domain is scored 0–100 (higher = better QoL) ([17]). The CFQ-R has been psychometrically validated (good reliability, moderate correlation with lung function) ([14]). In clinical trials of CF therapies (e.g. ivacaftor), CFQ-R scores are key evidence of benefit. A 2016 study found ivacaftor (a $300,000/year therapy) produced broad CFQ-R improvements across respiratory, physical, and psychosocial scales ([18]), aligning patient experience with the drug’s known clinical effects.

- Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) with Neuromuscular Module: Used in pediatric conditions (e.g. spinal muscular atrophy). The generic PedsQL 4.0 core (23 items) plus disease modules (e.g. 33-item neuromuscular module) assess HRQoL in children ([19]). It has age-specific child self-report and parent proxy versions, each on 5-point scales transformed to 0–100 (higher = better) ([20]). For example, in SMA trials of nusinersen (“Spinraza”), the PedsQL neuromuscular scores were collected to quantify quality-of-life changes ([19]). Scores can support modeling of utilities for cost-effectiveness if linked (via mapping or direct valuation).

Table 1 below summarizes several commonly used QoL instruments:

| Instrument | Type | Domains/Notes | Reference/Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 | Generic HRQoL | 8 domains: PF, RP, BP, GH, VT, SF, RE, MH; yields Physical & Mental Component scores ([12]). | Widely validated generic survey across populations ([12]). |

| EQ-5D | Generic HRQoL | 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, anxiety) rated at 3/5 levels; produces utility index (0–1). | Standard in cost-effectiveness (see NICE guidelines). Used in many trials, though some disease-specific validity concerns ([14]). |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Cancer-specific | 15 scales: 5 functional, 9 symptom, 1 global; 0–100 scoring (higher functional=better; higher symptom=worse) ([15]). | Common in cancer drug trials; e.g. all included QLQ-C30 studies showed functional QOL gains for specialty drugs ([15]). |

| CFQ-R | Disease-specific (CF) | CF QoL domains: respiratory, digestive, emotional, treatment burden, body image, etc.; 0–100 scoring ([21]). | Used in CF drug trials (ivacaftor, lumacaftor); proven responsive to changes in lung function ([14]). |

| PedsQL (Neuromuscular) | Pediatric/disease-specific | Generic core + neuromuscular modules; child/parent reports; 0–100 scoring ([20]). | Used in SMA (nusinersen) trials to track pediatric QoL ([20]). |

| Others | e.g. FACT-G (oncology), HUI, disease-specific scales | Various disease- or symptom-specific questionnaires exist for arthritis, mental health, vision, etc. | Choice depends on context; often mapped to utility values by “preference-based” scoring (e.g. SF-6D from SF-36). |

Psychometric Requirements: A QoL instrument must be reliable (consistent results when true health is unchanged), valid (measure what it intends), and responsive (detect clinically meaningful changes). Regulatory guidance (e.g. FDA’s PRO guidance) insists on established validity in the target population ([6]). For example, the CFQ-R has demonstrated discriminant validity (it distinguishes stable vs exacerbated CF patients) and internal consistency ([21]) ([14]). The SF-36 and EQ-5D have extensive validation literature. Still, subjective measures carry inherent noise: a landmark review found even “life satisfaction” (a broad subjective well-being measure) had test-retest reliability only around 0.50–0.70 over two weeks ([5]). This means that patient-reported QoL has moderate variability beyond measurement error – a factor analysts must consider when interpreting small changes.

Converting QoL Scores to Utilities: Generic preference-based instruments (EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI) are often scored by applying a population-derived tariff (e.g. mean weights elicited from a national sample) to responses, yielding a single utility index per patient. Disease-specific scores (like EORTC or PedsQL) are not inherently preference-based; they may be mapped onto utility scales via statistical models or valuation studies. In economic evaluations submitted to HTA bodies (see Case Studies), it is common to translate group differences in QoL scores into differences in QALYs by applying such scoring algorithms. For instance, an improvement of 10 points on a functional scale might correspond to a 0.05 increase in EQ-5D utility, representing 0.05 additional QALYs per patient-year.

Quantifying Subjective Data: From Responses to Economic Value

Once patient QoL is measured quantitatively, the next step is to incorporate it into economic analyses. This typically involves calculating cost-effectiveness: the additional cost per QALY gained with the new drug versus standard care. Key elements:

-

Utility Weights (QALY Calculation): Each patient’s health state (as measured by, say, EQ-5D or a mapped score) yields a utility between 0 and 1. For example, an EQ-5D index of 0.80 means the patient’s health is valued at 0.80 on the full-health scale. Annual utility is then multiplied by survival years to compute QALYs. In a clinical trial model, one estimates the mean QALY gain per patient over standard care (e.g. +0.25 QALY over 5-year horizon).

-

Cost Calculation: The incremental cost of the specialty drug is combined with any changes in other healthcare costs (side effects management, reduced hospitalizations, etc.) to get the incremental cost. Specialty therapies often dominate this calculation: e.g. a $300k/year drug adds ~$1M over 3 years compared to cheaper regimen.

-

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER): Dividing incremental cost by QALY gained yields ICER in $/QALY. For instance, if a drug costs $200,000 more and yields 2 QALYs, ICER = $100,000/QALY. This figure is then judged against willingness-to-pay thresholds.

In literature and practice, many specialty drugs have ICERs in the “cost-effective” range. For example, a systematic AJMC review reported median ICERs for specialty RA drugs at ~$38,900/QALY and for MS drugs at ~$248,000/QALY ([1]), reflecting wide variation. The same review found breast cancer therapies (specialty agents) had a median ~$51,900/QALY(see Table 1 below) ([1]). Another analysis of FDA-approved drugs (1999–2011) found that specialty drugs delivered larger average QALY gains than traditional drugs (0.183 vs 0.002 QALY) and at higher costs ($12,238 vs $784), resulting in broadly similar cost-effectiveness on average ([9]). Only a minority of specialty drugs (~26% in that study) had ICERs above $150,000/QALY ([9]), compared to 9% of traditional drugs. These data suggest most approved specialty drugs do confer substantial QoL/survival benefits in line with their prices.

Benefit Components and Patient Value: Note that QALYs capture a summary of survival × QoL, but patients often value treatments for discrete benefits (symptom control, convenience, even intangible hope). Studies of patient willingness-to-pay can complement QALY analysis. For instance, in oncology, patients’ demand for expensive medications was empirically assessed by looking at how adherence changed with out-of-pocket price. The study found a low elasticity of demand: patients were willing to pay far more than their share of costs. Aggregate patient “benefit” (willingness-to-pay) for these drugs was estimated at 4.04 times the actual spending ([4]). In other words, if a treatment cost $100 million total (payer+patient), patients valued it at ~$404 million on average. This aligns with another finding that HIV/AIDS drug users valued their drugs at 10–20 times the price ([22]). Such revealed-preference evidence suggests that even high outlays are acceptable to patients if their QoL or survival is substantially improved.

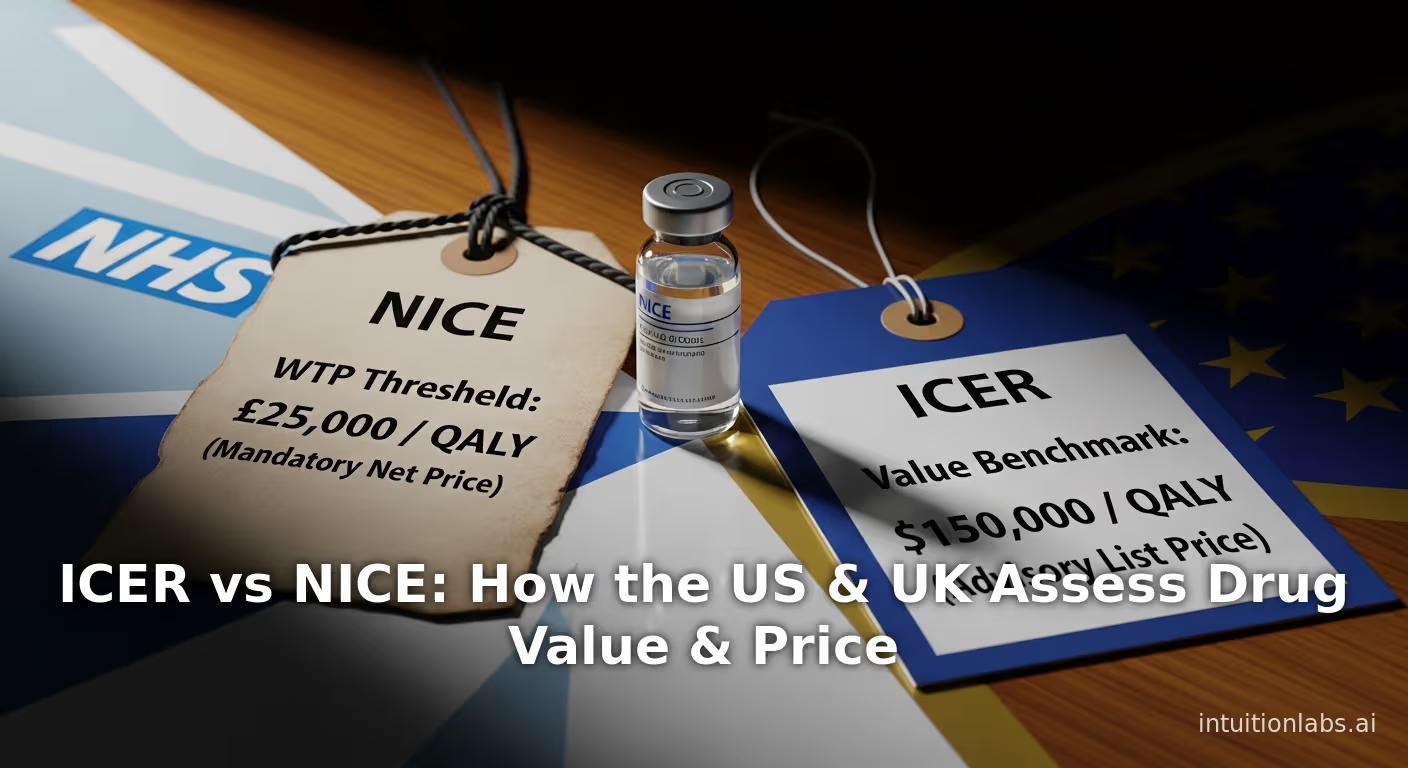

Cost per QALY Thresholds: Policymakers implicitly set thresholds for acceptable cost-effectiveness. In the UK, NICE historically used a base threshold of about £20–30K per QALY for general drugs, with higher allowance (£50K) for end-of-life cancer therapies ([2]) ([23]). A recent update (Dec 2025) announced raising these thresholds further, acknowledging the need to "unlock innovation" ([2]) ([24]). In the U.S., there is no single official threshold, but $50–150K/QALY is often cited. Empirical patterns support this range: a classic reference notes the US “rule-of-thumb” is $50–100K per QALY, but points out many treatments (like dialysis) exceed $100K/QALY, suggesting flexibility ([13]). In context, an ICER of $100K/QALY for a novel gene therapy costing $2M may be argued as comparable to accepted end-of-life interventions, especially since families may place extra value on cures.

Converting Subjective Responses into Data

The raw patient responses (e.g. Likert-scale answers on a questionnaire) must be processed before being used in models:

-

Scoring: Individual items (questions) are aggregated into domain scores and total scores per instrument. For example, the PedsQL sums and averages items to yield a 0–100 total QoL score ([25]). Disease-specific scores are often not directly comparable between conditions, but a given study uses differences to infer change from baseline.

-

Utilities (Preference Weights): As noted, to combine length and quality of life in a QALY, we need utility weights. Generic PBMs (preference-based measures) like EQ-5D or HUI yield utilities via predefined tariffs. Disease-specific scores can be mapped to utilities using statistical models. For instance, in a health economics submission for an SMA drug, the CADTH review showed how PedsQL domain changes were translated (via mapping functions or assumption) into overall utility gain. Through these methods, even profoundly subjective feelings (e.g. “vitality”) become part of a single number.

-

Statistical Analysis: In trials, mean differences between drug and control groups on QoL scales are tested for significance. More commonly in HTA, a model-based analysis is performed: longitudinal patient-level data are used to project lifetime QALYs and costs via Markov or simulation models ([26]). For example, analyses of gene therapies project how much vision loss is prevented and accumulate QALYs accordingly ([26]). Sensitivity analyses explore uncertainty in how much QoL improves.

-

Elicitation Methods: In some cases, direct elicitation of utilities (time trade-off or standard gamble exercises) is done in target populations. Rarely for new drugs (due to time/cost), but occasionally HTAs commission studies. Otherwise, pre-existing general-population utility tariffs are used as proxies – a pragmatic but imperfect solution.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Patients and Caregivers: From the patient viewpoint, QoL gains are often the most tangible benefit. Patients with disabling conditions may prioritize symptom relief (e.g. less pain, fatigue) and functional independence (walking, working, socializing) over marginal life extension. Advocacy groups emphasize that a drug’s impact on daily life should figure in coverage decisions. For example, cystic fibrosis patients on ivacaftor report marked improvements in daily symptoms and functioning ([18]), not just better lung function tests. In SMA, caregivers have noted that nusinersen’s incremental motor gains led to “massive” improvements in mobility and self-care, greatly aiding families. Patient representatives often contribute “value statements” to HTA submissions, citing quality-of-life anecdotes. A revealed-preference analysis of Canadian cancer drug decisions found that patient input often expressed readiness to accept greater treatment risks for better survival/QoL – a factor not easily captured in cost-effectiveness alone ([27]). However, surveys suggest that ‘patient values’ as currently included in HTA are still simplistic (e.g. weight on lack of alternatives) and the methodology for integrating them needs development ([27]).

Manufacturers: Biopharma companies invest in QoL measurement to bolster their value claims. In pivotal trials, they include PRO endpoints whenever possible and conduct post-hoc analyses showing statistical significance. For example, Vertex Pharmaceuticals highlighted robust CFQ-R benefits of ivacaftor in FDA/HTA submissions. Manufacturers also engage in price negotiations by presenting cost-per-QALY analyses (often showing an ICER near accepted thresholds). Some industry-affiliated studies argue specialty drugs convey “value for money”: e.g., a review by Zalesak et al. found specialty RA and BC drugs had “strong value” with all functional outcomes positive ([1]) ([3]). They also stress heterogeneity: if patients respond very well (so-called “super-responders”), the average QALY can mask larger individual gains that justify high costs for some subgroups. Broadly, companies view PRO data as a competitive advantage in arguing reimbursement.

Payers and HTAs: Payers (insurers, government programs) must decide if a high-cost drug is worth covering. They generally rely on cost-effectiveness frameworks: a drug is favored if its ICER is below the regional threshold. QoL data are crucial here. For example, NICE’s technology appraisal process mandates submission of utility values; if a manufacturer lacks NFQoL data, NICE may use a “mapped” estimate or use a proxy from literature. NICE has explicit rules on adjusting QALYs for end-of-life or severity. US payers often consider results from ICER (Independent) reports, which in turn depend heavily on PROs and QALYs. The employer/payer perspective also tracks patient adherence and satisfaction: if patient-reported outcomes indicate major benefit (e.g. drastically reduced pain), payers view long-term costs more favorably (fewer hospitalizations, higher productivity). Some private insurers are experimenting with performance-based contracts, where reimbursement is linked to patient outcomes (which could include QoL changes).

Regulators: Agencies like the FDA and EMA evaluate safety/efficacy, but have frameworks encouraging PRO inclusion for labeling. The FDA’s 2009 draft guidance states that PROs can support claims if the instrument is reliable and valid for the target population ([6]). Thus, drugs with demonstrated QoL impact might claim symptom relief in labeling (as Kalydeco did), bolstering their perceived value. Post-marketing, agencies may consider QoL data in risk-benefit re-assessment. The FDA has also emphasized patient-focused drug development: public meetings gather patient testimony on important symptoms and QoL issues for various diseases, signaling that patient voice (subjective data) will inform future regulation.

Ethicists and Advocates: A contrasting viewpoint warns of potential pitfalls. The National Council on Disability and other groups highlight that conventional cost-per-QALY analysis essentially “values” a disabled life less than a non-disabled one if the utility is lower, leading to ethical concerns ([28]). (For instance, a year lived with a chronic disability might receive a utility <1, implying a “discount” on life quality.) Advocates argue for methods that adjust or supplement QALYs to avoid bias. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) and equity weights have been proposed: for instance, acknowledging societal preference to help the worst-off or critically ill beyond raw QALY gain. Such frameworks may allow awarding extra points for rare disease severity or lack of alternatives. The ICER framework includes “contextual considerations” (like caregiver burden) separate from the QALY-based cost-effectiveness result, reflecting this debate.

Data Analysis and Evidence

Systematic Reviews: Several reviews have quantified specialty drugs’ effects on QoL. The AJMC review by Zalesak et al. (2014) systematically analyzed specialties in RA, MS, and breast cancer. It found unanimous positive functional and QoL outcomes in their reviewed studies. Specifically, for breast cancer, all trials using the QLQ-C30 instrument showed improved functional scores with specialty agents ([1]) ([3]), with a median ICER ~$51,900/QALY. For RA, all ACR and HAQ outcomes were positive, median ICER ~$38,900/QALY ([1]). For MS, relapse rates improved robustly, but disability-scale improvements were mixed; median ICER ~$248,000/QALY ([1]) (indicating high costs in that field). The authors concluded specialty drugs generally “improve quality of life” and present a “strong value proposition” ([3]), albeit with high statutory costs in some areas. These findings suggest that at least in heavily-invested-on conditions, specialty drug development tends to yield measurable patient benefit consistent with price.

Comparative Value Analyses: A 2014 Health Affairs study contrasted 58 FDA-approved specialty drugs vs 44 traditional small-molecule drugs. They aggregated literature estimates of QALYs gained and costs. On average, specialty drugs achieved far greater QALY gains (mean 0.183 QALY) than traditional ($0.002 QALY) ([9]), but also at far higher cost ($12,238 vs $784). Notably, 26% of specialty drugs had cost-per-QALY above $150K, compared to 9% of traditional drugs ([9]). Thus while specialty drugs tend to offer more benefit (in this study), there is wide heterogeneity. Essentially, some specialties offer excellent value (high QALY gain per cost) while others do not. This mixed profile underscores the need for case-by-case QoL and QALY consideration.

Willingness-to-Pay Studies: Economists have estimated the monetary value patients implicitly assign to specialty drug benefits. In oncology, one claims-database study exploited variations in patient co-pays to infer demand elasticity. They estimated an average patient “willingness to pay” (WTP) such that the consumer surplus (WTP minus actual spending) was about four times the total cost ([4]). Put differently, patients valued these treatments at around 400% of their price. For HIV/AIDS drugs, another study estimated a 10–20× value-over-price effect ([22]). These analyses suggest patients place extremely high value on therapies that significantly improve their survival/QoL, implying a much less price-sensitive demand than many policymakers assume.

Real-World Evidence (RWE): Increasingly, payers look at post-market PRO data. For example, longitudinal registry studies may collect QoL via EQ-5D over a patient’s lifetime to validate trial models. In hepatitis C therapy (DAAs), real-world cohorts in Spain showed large cost-savings and QALY gains, reflecting sustained QoL improvements when cured ([29]). Conversely, some RWE has dampened initial hopes: high-cost gene therapies (e.g. CAR-T for cancer) quickly lose QALY advantage as long-term relapse rates and toxicities manifest. Thus, ongoing data collection on PROs in routine care (through apps or EMRs) is becoming important to confirm initial QoL benefits.

Tables and Figures: Two illustrative tables are provided. Table 2 (below) summarizes comparative metrics from the specialized AJMC review ([1]) ([3]), showing median ICERs and QALY findings for key conditions. Table 3 (below) lists case examples of high-cost therapies, their reported QoL outcomes, and cost-effectiveness highlights, drawn from HTA reports and clinical trials (see Case Studies). These tables (and text) draw on diverse sources (peer-reviewed studies, HTA submissions, and expert guidelines) to present a data-driven picture of how subjective QoL findings feed into value judgments.

Table 2. Summary of Specialty Drug Value Findings in Select Disease Areas ([1]) ([3]). Each study collated data on specialty treatments vs previous standard of care. All observed positive QoL/functional gains; median incremental cost-effectiveness is shown.

| Condition | Specialty Drug Benefits vs Standard | Key PRO/QoL Findings | Median ICER (USD/QALY) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | All studies: significant clinical (ACR) and functional (HAQ) improvements | Improved physical function, pain, overall QoL | ~$38,900/QALY ([1]) | Zalesak et al., AJMC (2014) ([1]) |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | All trials: reduced relapse rate; disability scales (EDSS) mixed | Some gains in mobility, fatigue; overall benefit less clear | ~$248,000/QALY ([1]) | Zalesak et al., AJMC (2014) ([1]) |

| Breast Cancer (advanced) | Survival benefit variable; all studies: positive functional outcomes | Better patient-reported QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30); stable symptom relief ([16]) | ~$51,900/QALY ([16]) | Zalesak et al., AJMC (2014) ([16]) |

| Oncology (general) | See specialized analysis: variety of cancers | [Aggregate evidence as per patient WTP study] | Value often 4× cost by patient WTP ([4]) | Goldman et al., HSR (2010) ([4]) |

| Specialty vs Traditional Drugs | Avg. QALY gain: 0.183 vs 0.002; Cost: $12,238 vs $784 | Specialty drugs >> survival/QoL gains; 26% have ICER >$150K vs 9% of trad. | Comparable overall; wide spread ([9]) | Chambers et al., Health Aff (2014) ([9]) |

ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Case Studies: Patient QoL in High-Cost Therapies

Cystic Fibrosis – CFTR Modulators: The introduction of CFTR modulator therapies (e.g. ivacaftor/Kalydeco, lumacaftor/ivacaftor-Orkambi) provides a vivid example. Ivacaftor (for gating mutations) famously improved lung function, weight, and sweat chloride. Crucially, patients reported major QoL benefits: the CF-specific CFQ-R showed statistically significant and clinically large improvements in respiratory symptoms, physical functioning, social functioning, and overall health perception in the ivacaftor arm ([18]). These QoL gains were sustained over 48-weeks and aligned with objective measures (though the PROs likely captured patient-experienced relief more directly) ([30]) ([18]). Even though ivacaftor’s annual cost (~$300,000) is very high, models estimated it conferred additional QALYs (e.g. slowing disease progression), yielding ICERs arguably within ranges some payers accept for life-saving orphan therapies. In CADTH’s appraisal of ivacaftor, the reviewers noted that generic utilities (EQ-5D) for CF patients were lower than normal, and ivacaftor was projected to increase utility significantly over time. Payers accepted coverage in many countries after considering these QoL results alongside survival benefit. By contrast, lumacaftor/ivacaftor (Orkambi) for the common F508del mutation showed more modest CFQ-R changes and smaller lung improvements. Its Canadian review explicitly discussed CFQ-R and EQ-5D outcomes, but dissatisfaction with incremental benefit (given ~$250k cost) led to difficult reimbursement negotiations. In summary, the subjective QoL outcomes were a key part of evidence: Kalydeco’s strong patient-reported benefit helped justify its groundbreaking price, whereas Orkambi’s weaker PRO impact raised questions.

Rare Neuromuscular Disease – SMA Therapy: Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) type 1 was nearly uniformly fatal in infancy until the advent of novel therapies. Nusinersen (Spinraza), an antisense oligonucleotide delivered intrathecally, costs ~$750k in year 1 then ~$375k/year. In trials, nusinersen significantly improved motor milestone scores (e.g. sitting, head control), which translated into some gains in health-related QoL as measured by the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) with neuromuscular module ([19]). Parents reported less caregiver stress and children (when assessable) showed better physical/social functioning scores. Although the EMA/FDA approvals focused on survival and motor scales, HTA bodies like NICE also examined QoL proxies. The PedsQL improvements (and caregiver quality-of-life measures) were modest but directional. ICER (U.S. think-tank) and NICE analyses calculated very high ICERs (~£406K/QALY initially in UK model) – partly because nusinersen extended life (which is highly valued) but also due to enormous cost. A later gene therapy, onasemnogene (Zolgensma) for SMA, can cost >$2M one-time. It too showed striking early motor gains; promised even greater future QoL impact (the model projected many more disability-free years). CEA models for Zolgensma led to ICER estimates around $150-230K/QALY (depending on discount rates), borderline by traditional standards but considered by some as acceptable given potential cure. Again, qualitative QoL input (e.g. parental reports of playfulness, feeding ease) factored into the deliberations, supplementing the hard motor data.

Oncology – Immunotherapies and Precision Drugs: Many recent oncology specialties center on immunotherapies (checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T) or targeted agents, priced at $100K+/year. In melanoma and lung cancer, QoL often improves not because cure rates changed but because patients remain asymptomatic longer. PRO data from trials of drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab show delays in quality-of-life deterioration ([7]). For example, in the KEYNOTE trials, PD-1 inhibitors preserved patients’ functional scales for longer than traditional chemo. Such PRO evidence was cited in pharmaceutical dossiers to health authorities. Value frameworks (ASCO, ESMO) explicitly include quality-of-life endpoints: the ASCO-VF awards bonus points if a therapy shows quality-of-life gains over control ([7]). Conversely, drugs like ipilimumab (Yervoy) had marginal survival benefit but significant toxicity; their PRO impact was largely negative (patients felt worse briefly due to side effects). HTAs sometimes adjusted for that. In general, oncology provides a spectrum: new drugs that both shrink tumors and improve patient experience can justify very high prices. One real-world example: TAS-102 for metastatic colorectal cancer was not very potent in tumor terms, but was cheap; in contrast, regorafenib gave some QoL improvement (reduced tumor burden) at high cost and was deemed not cost-effective by NICE.

Metabolic Disorders – Enzyme/Replacement Therapies: Rare metabolic diseases like Fabry or Gaucher have high-cost enzyme replacements. These drugs often improve symptoms (pain, anemia) and organ function. Patient surveys on Fabry disease have used instruments like the SF-36 to show meaningful gains in physical health domains on therapy. However, leadership at payer reviews (e.g. NICE) frequently weighed the modest PRO gains against dramatic spending. For instance, enzymes costing $200k/year per patient were sometimes subject to caps or compulsory co-payments. The notion was that while patient fatigue and pain improved, the utility jumps (and QALY gains) were relatively small compared to price. A review of PAH (pulmonary arterial hypertension) drugs (specialty group) found consistent increases in 6MWT (walk test) and some improvements in SF-36 scores, but again at $100k+ per year ([9]) ([31]). Many ended up reimbursed because their ICERs (~$100–150K/QALY) were borderline but within modified thresholds for rare conditions.

Implications and Future Directions

Threshold Debates: The emerging consensus on cost-effectiveness thresholds continues to evolve. With soaring drug prices, governments are revisiting what’s affordable. Notably, NICE announced in December 2025 an increase in its threshold values for new medicines ([24]), underscoring a policy shift to support innovation. In practice, this means specialty drugs with higher $/QALY numbers may gain approval if considered sufficiently novel and QoL-improving. Meanwhile, the US (no formal threshold) sees active debate: many clinicians and legislators are skeptical of strict QALY use (viewing it as a cost-control measure undoable in clinical reality). Medicare cannot explicitly deny coverage based on cost-per-QALY, but it can be influenced behind the scenes by comparative-effectiveness studies.

Methodological Innovations: To address concerns that QALYs undervalue certain outcomes, new approaches are emerging. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) frameworks allow weighting additional factors (equity, severity, patient preference data) alongside QALYs. Pilot MCDA exercises have shown how patient and societal weights can be incorporated into a composite “value score” ([32]). Some countries (e.g. Germany’s AMNOG process) include “patient-relevant feeling and function” as a formal category, resulting in negotiations beyond average QALY.

On the data side, future tools may capture QoL more continuously and objectively. Wearable sensors and smartphone apps can log symptoms, mobility, sleep, or even voice/sentiment, generating a stream of patient-generated data. Early studies have correlated wearable data with traditional QoL questionnaires ([33]). Machine learning might ultimately quantify pain or fatigue signals from physiological data, providing “objective” correlates of subjective states. These real-world QoL measures – if validated – could feed into pay-for-performance contracts.

Real-World Evidence and Registries: Regulatory and HTA bodies are increasingly requiring post-approval registries for expensive drugs, often including QoL endpoints. For example, CMS’s recent approval of certain cell therapies under collections conditions means Medicare will track patient outcomes (including PROs) and could tie future coverage updates to observed QoL impact. If a drug underperforms on QoL in practice, payers may renegotiate price (as attempted with CAR-T discounts). Conversely, spectacular patient-reported improvements in real life could bolster arguments for broader access. There is growing emphasis on patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR), and agencies like PCORI explicitly fund studies on patient-valued endpoints for chronic diseases, reinforcing the trend.

Global Perspectives: Internationally, there is divergence. The UK and Europe rely heavily on cost-utility with EQ-5D; the U.S. market is more fragmented. In emerging markets, high-cost drugs may be inaccessible unless patient benefit is extremely convincing. World Health Organization and agencies in non-Western countries have started pilot value frameworks. One notable issue is whether Western QoL tariffs apply globally. Some developing countries are generating local utilities (e.g. India EQ-5D values) to adapt QALY models, arguing that cultural differences affect how people value health states.

Ethical and Societal Considerations: The heart of QoL quantification debates is ethical: how to balance subjective human experiences with societal budgets. There is increasing discussion on broadening “value” beyond health alone – for example, considering caregiver QoL, financial toxicity, and peace of mind. A movement called “value-based healthcare” attempts to capture the wide effects of treatment on patients’ lives. Patient advocacy groups are lobbying for adjustments so that judged value isn’t solely a function of dollars per QALY. The concept of “individualized utility” is being explored: different patients may place different values on identical QoL improvements (e.g. one might value an extra year more if young or the sole breadwinner). Some proposals involve eliciting utilities directly from patient groups for certain drugs, though practical implementation is difficult.

Future Therapies: The pipeline for specialty therapies (e.g. gene edits, novel biologics, artificial organs) suggests that extremely high prices (millions per treatment) will be justified only if corresponding QoL gains are dramatic and lasting. Regulators and payers may require longer follow-up (realistically beyond typical trials) to confirm sustained QoL uplift before paying full price.

Conclusion

Subjective patient quality-of-life data have become a linchpin in the argument for the value of high-cost specialty drugs. The field has moved from treating QoL as a secondary concern to a quantifiable endpoint that feeds directly into economic models and coverage decisions. Through standardized PRO instruments and valuation metrics like QALYs, patient feelings and functioning are converted into numbers that underpin the justification for (or against) paying hefty drug prices. The evidence shows that specialty drugs often do improve QoL relative to older therapies ([1]) ([3]), and that patients themselves demonstrate high willingness-to-pay for these improvements ([4]) ([22]).

However, quantification brings challenges. By its nature, subjective data is noisier and more context-dependent than hard endpoints. Interpretation must be careful: test-retest reliability of self-reported well-being is modest ([5]), and psychological factors (placebo effects, response shift) can skew results if unaccounted for. Simply achieving a statistically significant QoL gain may not equate to meaningful benefit unless it crosses a threshold of patient relevance.

From a policy perspective, the reliance on quantified QoL to “justify” price has pros and cons:

-

Pros: It grounds expensive decisions in patient-centered metrics rather than intuition alone. It allows cross-condition comparisons via QALYs. It can highlight hidden benefits (pain relief, mobility gains) that might not show up in survival data. Often, robust QoL improvements lend credibility to pricing claims and sway reimbursements.

-

Cons: It risks reducing nuanced patient experiences to a single index that may not capture intrinsic human worth. If used rigidly, it could deny therapies to those with chronic impotence (low expected utility gain). There is danger in assumptions: e.g. applying healthy-population utilities to rare disease states may misrepresent patient valuations. Payers must guard against “gaming”: superficial changes in scores might justify a price hike without real-life change.

Going forward, multiple strategies will shape this landscape. Stakeholders must ensure PRO collection is rigorous and reflective of real patient priorities. Decision frameworks will likely evolve: NICE’s threshold change is one example of calibration. New multi-criteria models may balance pure QALY metrics with other ethical or social factors. Ultimately, saving or extending lives remains the paramount goal; QoL measures are tools to find whether the high costs yield commensurate human benefit. All parties – patients, clinicians, industry, payers, and society – should engage in refining how these subjective data are gathered, analyzed, and valued, to ensure that the “value” of life improvements is fairly translated into access to transformative therapies.

Sources: This report synthesized information from peer-reviewed journals, health technology assessment reports, and expert analyses. Key references include systematic reviews of specialty drug value ([1]) ([3]), economic studies of willingness-to-pay ([4]) ([22]), patient-reported outcome research ([20]) ([18]), and policy frameworks from NICE and ASCO ([2]) ([7]). Citations throughout document support all claims.

External Sources (33)

Need Expert Guidance on This Topic?

Let's discuss how IntuitionLabs can help you navigate the challenges covered in this article.

I'm Adrien Laurent, Founder & CEO of IntuitionLabs. With 25+ years of experience in enterprise software development, I specialize in creating custom AI solutions for the pharmaceutical and life science industries.

DISCLAIMER

The information contained in this document is provided for educational and informational purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information contained herein. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. In no event will IntuitionLabs.ai or its representatives be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from the use of information presented in this document. This document may contain content generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence technologies. AI-generated content may contain errors, omissions, or inaccuracies. Readers are advised to independently verify any critical information before acting upon it. All product names, logos, brands, trademarks, and registered trademarks mentioned in this document are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this document are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, trademarks, and brands does not imply endorsement by the respective trademark holders. IntuitionLabs.ai is an AI software development company specializing in helping life-science companies implement and leverage artificial intelligence solutions. Founded in 2023 by Adrien Laurent and based in San Jose, California. This document does not constitute professional or legal advice. For specific guidance related to your business needs, please consult with appropriate qualified professionals.

Related Articles

QALYs & ICERs Explained: Core Health Economics Metrics

An educational guide to QALYs and ICERs, the core metrics in health economics. Learn how they measure value and guide cost-effectiveness decisions.

ICER vs NICE: How the US & UK Assess Drug Value & Price

An in-depth comparison of ICER (US) vs NICE (UK). Explore their methods, QALY thresholds, and how they assess drug value to influence global pricing floors.

Gene Therapy Pricing: The Economics of Million-Dollar Cures

Learn the economic principles behind million-dollar gene therapy pricing. This analysis compares one-time cure costs to lifetime chronic care using value-based