Understanding Drug Formularies, Benefits, and ePA in the US

Executive Summary

Formulary and benefits management, along with prior‐authorization (PA) requirements, are central facets of U.S. pharmacy benefits systems designed to control drug costs and ensure appropriate use of medications ([1]) ([2]). This report provides an in-depth analysis of how formularies are structured and managed, how pharmacy benefits and cost-sharing tiers operate, and how electronic prior authorization (ePA) systems are being implemented in the United States. Historically rooted in hospital pharmacy and expanded by the rise of managed care in the late 20th century ([1]) ([2]), formularies today rely on Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees (often run by insurers or Pharmacy Benefit Managers) to decide which medications are covered and at what level of restriction ([3]) ([4]). Formularies may be “open” (wide coverage) or “closed” (limited list) and typically use tiered cost-sharing to encourage generics and preferred products ([4]) ([5]). These structures shape patient out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. median copays of about $11 for generics vs. $59–$123 for higher-tier drugs ([6])) and dictate which uses of brand or specialty drugs require authorization or step therapy.

Prior authorization policy evolved alongside formularies as a utilization-management tool. Insurers mandate PA for many high-cost or complex drugs to confirm medical necessity and control spending ([7]) ([2]). While PA can negotiate manufacturer discounts and encourage safer prescribing, manual PA workflows are widely regarded as burdensome. Surveys show almost all prescribers face PA delays (e.g. 96% of oncologists report patient treatment delays due to PA) ([8]), and providers spend substantial time on PA tasks. Electronic prior authorization (ePA) standards have been developed by NCPDP to streamline PA requests within e-prescribing systems. Field pilots demonstrated that ePA can enable “end-to-end” approvals in under five minutes with outcomes matching manual PA ([9]). However, national adoption has been slow: one estimate finds only ~21% of PA transactions fully electronic ([10]). High-level surveys and studies indicate mixed impacts of ePA – it can speed decision turnaround and reduce paperwork (and CMS projects $15 billion saved over a decade from PA reforms ([11])), but real-world implementations have so far not substantially raised prescription fill rates ([12]) ([13]).

This report examines multiple perspectives – payers, providers, patients, and regulators – using data from peer-reviewed studies, government reports, industry analyses, and legislation. We review formulary types and tier designs, present data on payer cost-sharing, and describe the technical standards (NCPDP SCRIPT, HL7 FHIR APIs) enabling electronic formulary and PA workflows. We cite case examples and empirical research on PA and ePA outcomes, including Medicare studies showing PA rules can sharply delay care ([14]) ([15]). Finally, we discuss regulatory developments (e.g. CMS ePA mandates, state laws) and future directions (real-time benefit checks, payer/provider portals) that will shape how formularies, benefits and PA are managed.

1. Introduction and Background

Prescription drug spending in the U.S. has grown dramatically over recent decades, prompting insurers and managed care organizations (MCOs) to adopt formularies and utilization-management tools to contain costs ([1]) ([2]). For example, U.S. health expenditures rose from $26.8 billion in 1960 to $949.4 billion in 1994 (with drugs accounting for 8.2% of costs) ([1]). This inflation coincided with a major shift from fee-for-service to managed care – HMO enrollment jumped from 6 million in 1976 to ~58 million by 1995 ([1]). As MCOs expanded, they implemented outpatient drug formularies for the first time outside of hospitals ([1]) ([16]).

The formulary concept traces back to hospital pharmacy practice: by 1965 the Joint Commission for Hospital Accreditation required hospitals to have Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P&T) committees to manage inpatient drug lists ([17]). A hospital formulary (approved drug list) enabled consistent therapy and inventory control. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as insurers faced rising outpatient drug costs, they adopted similar P&T committees and formularies for community patients ([18]) ([16]). Legislation also began to shape benefits: for instance, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (creating Part D) mandated that plans maintain comprehensive formularies reviewed by CMS. By contrast, Medicaid programs must follow state-determined preferred drug lists and generic substitution rules. Overall, formularies have become an “integral component of the managed care pharmacy landscape” ([19]).

Simultaneously, prior authorization (PA) emerged as a utilization-management practice. Under PA policies, insurers require providers to obtain approval before filling certain prescriptions (usually high-cost or high-risk drugs). PA aims to ensure that therapy is medically necessary and cost-effective. In managed care, panelists note PA “is an essential tool to ensure the appropriate use of medical and pharmaceutical technologies” and to improve patient safety ([2]).By steering patients toward step therapy (cheaper drugs first) or generics, PA helps plans leverage rebates and discounts from manufacturers ([7]) ([2]). Indeed, researchers observe that PA and formularies give payers substantial negotiating power: one commentary states PA “ensures high-cost or high-risk medications are dispensed only to patients for whom they are clinically indicated,” and it often helps plans negotiate larger price rebates (thereby lowering their net costs) ([7]).

However, manual PA processes are time-consuming. The typical workflow involves the prescribing clinician or pharmacist filling out lengthy forms (often faxed) and waiting for a payer decision. Surveys consistently show nearly all practices face PA burdens: for example, a 2022 oncologist survey found 96% had patient treatment delays from PA requirements ([8]). Physicians report spending hours each week on PAs (often by nursing or admin staff), contributing to burnout. Industry analyses estimate substantial administrative costs: one older report suggests ambulatory practices spend about $80,000 per physician per year dealing with payers, much of it attributable to PA and other steps ([9]). These delays can directly affect care – studies link PA requirements to medication non-adherence and poorer outcomes in some cases.

In recent years, the promise of information technology to streamline PA has driven new standards and regulations. In 2014-2015, the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) published the first electronic prior authorization (ePA) transaction standards, and industry forums (led by AMCP, Surescripts, and others) explored implementations ([20]) ([21]). At the same time, broader health IT mandates began to require electronic exchange of benefit and drug data. For example, CMS’s 21st Century Cures Act (2016) directed HHS to adopt standards for electronic PA, and in 2024 the CMS finalized interoperability rules mandating HL7 FHIR APIs for health plans to share PA status and drug coverage information with providers (with timelines through 2027) ([22]) ([23]). These regulatory changes reflect a national push to move PA and formulary management from paper/fax into the digital realm, integrating it with electronic prescribing and EHRs.

Against this backdrop, this report examines how formularies and pharmacy benefits work, and how ePA is being adopted and implemented in the U.S. We first detail formulary design and its effects on patient costs. Next, we review the development of electronic formulary data standards and real-time benefit tools. Then we analyze prior authorization: its benefits and burdens, ePA standards and adoption, and evidence from studies and pilots. We include key statistics, stakeholder perspectives, case examples, and cite a wide array of sources. Finally, we discuss policy developments and future directions in formulary and ePA.

2. Formulary and Pharmacy Benefit Design

Pharmacy benefits are usually managed by insurers, employer plans, or government programs (e.g. Medicare Part D, Medicaid). A central tool is the formulary – a codified drug list determining coverage and cost-sharing. Formulary design is governed by a P&T (Pharmacy & Therapeutics) committee, which may be internal to a health plan or provided by a contracted Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) ([24]) ([25]). The P&T committee’s role is to “optimize patient care through safe, appropriate, effective, and affordable medication use” by selecting which drugs are covered and under what conditions ([3]). Committees typically include physicians, pharmacists, and sometimes specialists in pharmacology or pharmacoeconomics ([26]) ([25]).

2.1 Formulary Types and Structure

Formularies may vary widely, but common distinctions are open vs closed and tiered designs ([4]) ([5]).

-

Open Formulary: An open formulary is broad and liberal. It generally covers all or almost all drugs, and uses few direct restrictions. An open formulary may highlight “preferred” drugs (often generics), promoting them through doctor communications and pharmacy system prompts, but allows coverage of non-preferred drugs on request ([27]). Because it imposes few barriers, an open formulary has minimal impact on utilization patterns. In practice, open formularies offer choice but do relatively little to curb costs, since nearly any medically necessary drug will be covered (often with a higher patient cost-sharing if it is non-preferred) ([27]).

-

Closed Formulary: A closed formulary severely limits covered medications. It typically includes only a definitive list of 300–1,000 drug products ([16]). Only drugs on the formulary (and usually their generics) are covered by the plan; non-formulary drugs require special authorization. By covering only select products (often chosen for cost-effectiveness), a closed formulary gives the plan strong leverage to negotiate prices. However, it requires well-defined PA or medical necessity review for any excluded drug ([16]). Closed formularies often still include multiple options per therapeutic class, but alternatives outside the formulary aren’t reimbursed without authorization.

-

Tiered (Open/Closed hybrid): Most modern insurance plans use a tiered formulary. Here, drugs are placed into tiers (usually 2–4 levels) with different copayment or coinsurance requirements. A typical arrangement might have Tier 1 = generics (low copay), Tier 2 = preferred brands (moderate copay), Tier 3 = non-preferred brands (higher copay), and Tier 4 = specialty or expensive items (highest copay/coinsurance). Tiered formularies allow broad coverage (since even expensive drugs are covered in some tier) while steering patients toward lower tiers whenever possible. For example, if a generic (Tier 1) is available, the patient pays much less than for an equivalent brand (Tier 3). Tiered designs balance access and cost-sharing and are extremely common: a 2019 survey found 91% of covered employer-plan workers were in plans with tiered drug cost-sharing ([28]).

-

Other Variations: Other formulary features include “preferred brands” (in which the plan has multiple brands on formulary but designates one as preferred) and “negative lists” (explicitly forbidden drugs). Plans may also mandate generic substitution (requiring cost-sharing waivers for pharmacists substituting an approved generic) and implement quantity limits or step therapy (required trials of cheaper drugs before expensive ones). In designing the formulary, the P&T committee considers clinical efficacy, safety, and cost for each drug. They may hold subcommittee deliberations and consult pharmacoeconomic data ([29]) ([30]). The work is dynamic: as new drugs enter the market or prices change, P&T committees periodically update the formulary and corresponding management protocols ([30]) ([31]).

2.2 Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

Pharmacy Benefit Managers are intermediaries that many insurance plans use to manage their drug benefit. PBMs typically develop “template” formularies and negotiate drug prices for multiple health plans. A PBM’s P&T committee creates a master formulary based on its network’s needs ([25]). An insurer (MCO) may then adopt this master formulary wholesale or tailor a subset. Even when an MCO has its own P&T committee, PBM staff often provide much of the clinical and financial research to support formulary decisions ([25]). Thus, many plans rely on industry-wide PBM formularies for initial drug coverage strategy.

When a prescriber orders a non-formulary drug, the PBM claims adjudication system typically flags it. Under traditional workflows, the pharmacy may be notified with an electronic “non-covered” message during claim adjudication. The pharmacist would then inform the physician or patient that authorization is needed. Some systems automatically prompt a pharmacist or prescriber to consider a formulary alternative. For example, one analysis notes that PBM systems can send an “RxChange” message to the prescriber (via e-prescribing networks) suggesting a covered alternative if the original choice is not on formulary ([32]). In practice, this requires extra communications: contacting the doctor, submitting a PA, re-prescribing, and adjudicating a new claim. PBMs often issue “report cards” to physicians comparing their prescribing of preferred vs non-preferred drugs, further encouraging formulary adherence ([33]). These processes are labor-intensive and have driven interest in electronic tools to streamline them ([34]) ([35]).

2.3 Cost-Sharing and Benefit Design

Formulary placement directly influences patient cost-sharing. In tiered plans, each tier has a specified copayment (fixed dollar) or coinsurance (percentage). For example, in 2019 the average copay for Tier 1 generics was about $11, rising to $33 for Tier 2 and $59 for Tier 3 drugs ([6]); specialized Tier 4 drugs averaged $123 copay ([6]). Many plans also impose deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums specifically for drugs. In 2019, about 69% of workers in plans with a separate drug deductible had an annual drug deductible (average roughly $194) ([36]). With the growth of high-deductible health plans, patient out-of-pocket costs for many medications—especially brand and specialty drugs—have increased in recent years.

Plans may structure benefits to favor generics (sometimes offering zero copay generics) or to steer volume toward mail-order 90-day supplies (often at lower co-pays) ([37]). Some employers experiment with value-based insurance design: one survey described “benefit-based copays” where very high-risk/most beneficial drugs have lower copays ([38]). In general, formularies and tiered copays are designed to align patient incentives with cost-effective prescribing. However, critics argue they can be confusing and limit access. Indeed, the ACA requires that prescription drugs be an essential health benefit, and CMS oversees Part D formularies to ensure at least one drug per category is covered, mitigating extreme designs.

Finally, formulary management uses utilization restrictions beyond copays. Quantity limits (e.g. 30 tablets per month on certain chronic drugs) are another common tool. Step therapy (also called “fail-first”) requires patients to try a preferred/bioequivalent medication before the plan covers the originally prescribed drug. These restrictions are typically implemented via PA or similar processes. For example, if a brand-name biologic is subject to step therapy, the prescriber must upload documentation (or complete an ePA form) indicating the patient has tried FDA-designated first-line therapies. The formulary P&T committee defines these protocols (including what documentation is needed) as part of the formulary’s PA policies ([5]) ([39]). Often, payers provide a standard PA form listing the required information; submitting incomplete forms (e.g. only verbal info) is usually rejected ([39]).

Table 1: Examples of Formulary Strategies and Features

| Formulary Strategy | Description | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Open Formulary | Broad coverage; few restrictions. | Limited to preferred communication. Does not strongly control cost ([27]). |

| Closed Formulary | Coverage only for drugs on a specific list (300–1000 products) ([5]). Requires documentation for non-formulary drugs. | High control on utilization; non-preferred requires PA ([5]). |

| Tiered Copay Structure | Drugs placed in tiers with ascending cost-sharing for higher tiers. | E.g., Tier 1 = generics ($10–11), Tier 2 = preferred brands ($30–33), Tier 3 = non-preferred brands (~$59), Tier 4 = specialty (~$123) ([6]). |

| Step Therapy | Require trial of first-line (often lower-cost) drug before others. | Must fail on generic statin (Tier 1) before payfor brand (Tier 2). |

| Prior Authorization | Require insurer approval before covering certain drugs. | Common for expensive or high-risk drugs (see Section 4). |

| Generic Substitution | Mandate dispensing of therapeutically equivalent generic unless opt-out. | Saves costs (e.g. statin generics offered at $0 co-pay in some plans). |

| Quantity Limits | Limits number/dose per time period for certain drugs. | E.g. 30 days of ADHD medication at a time; 90-day supply via mail order ([37]). |

2.4 Impact on Patients and Spending

Formulary and benefit design strongly influence patient behavior and plan costs. By channeling utilization to lower-cost drugs, formularies aim to encourage adherence to effective therapy while keeping overall spending down. Studies show that formulary restrictions can meaningfully reduce spend on higher-tier drugs. A systematic review found that formulary restrictions (PA, step therapy, limiting coverage) generally lower pharmacy costs for payers ([40]). However, these controls can also have patient downsides. Restricting coverage may delay care if patients wait for authorization, and some evidence suggests that strict formulary controls on essential drugs (like statins) can inadvertently reduce usage and worsen outcomes ([40]).

In practice, plans try to balance these effects. For example, Medicare Part D regulations require “protected classes” (like cancer drugs, HIV drugs) have wide coverage, limiting formulary exclusion of essential medicines. State Medicaid programs also often impose open or preferred drug lists for core medications. Nevertheless, formulary changes can trigger cost shifts: if a drug moves from Tier 2 to Tier 3, patients may face sharply higher copays, potentially causing some to delay or abandon therapy. Health economists have noted concerns: one study in cancer treatment found adding a PA requirement increased therapy discontinuation odds by 7-fold ([14]). Another JCO analysis concluded that new PA policies “wasted time and undermined access to care” for patients on stable regimens ([15]).

Overall, formulary and benefit decisions are a key part of insurance plan practices, wielding considerable influence over which medications patients use and at what cost. They are developed and updated continuously by P&T committees, PBMs, and regulators, aiming to ensure that medication use is evidence-based and cost-conscious. In the next section, we examine how modern technology is bringing this formulary data directly into the electronic prescribing workflow to further optimize medication selection at the point of care.

3. Electronic Formulary and Real-Time Benefit Data

Traditionally, formulary information was only available in print or via call centers. Clinicians often learned coverage details indirectly (e.g. when a pharmacist called about a PA). In the past decade, standards and tools have been developed to deliver formulary and benefit info electronically at the point of prescribing, enabling more informed decisions and reducing surprises.

3.1 Formulary & Benefit (F&B) Standard

The NCPDP Formulary & Benefit (F&B) Standard is a key enabler of electronic formulary data. NCPDP, a standards body, launched the F&B transaction in 2013 to allow payers/ PBMs to transmit formulary coverage, cost-sharing, and PA requirements to prescriber systems ([41]). In practice, when a clinician writes a prescription in an EHR or e-prescribing system, the software can query the payer (via NCPDP SCRIPT F&B) for that patient’s coverage. The response can include answers to questions like: Is this drug covered? What formulary tier is it on? What would the copay be? Is prior authorization required? F&B queries use the SCRIPT standard (HTTP API) and return benefit details at the group or member level.

Regulations now require use of F&B-type data. In CMS’s interoperability final rule (2024), plans must use either NCPDP F&B 3.0 or an equivalent standard when sending formulary/benefit data to prescribers ([23]). Indeed, the ONC’s published standards list shows NCPDP F&B v3.0 as a federally required standard for transmitting pharmacy benefit information ([23]). Thus, modern EHRs and e-prescribing modules increasingly support F&B transactions, integrating coverage checks before a prescription is finalized.

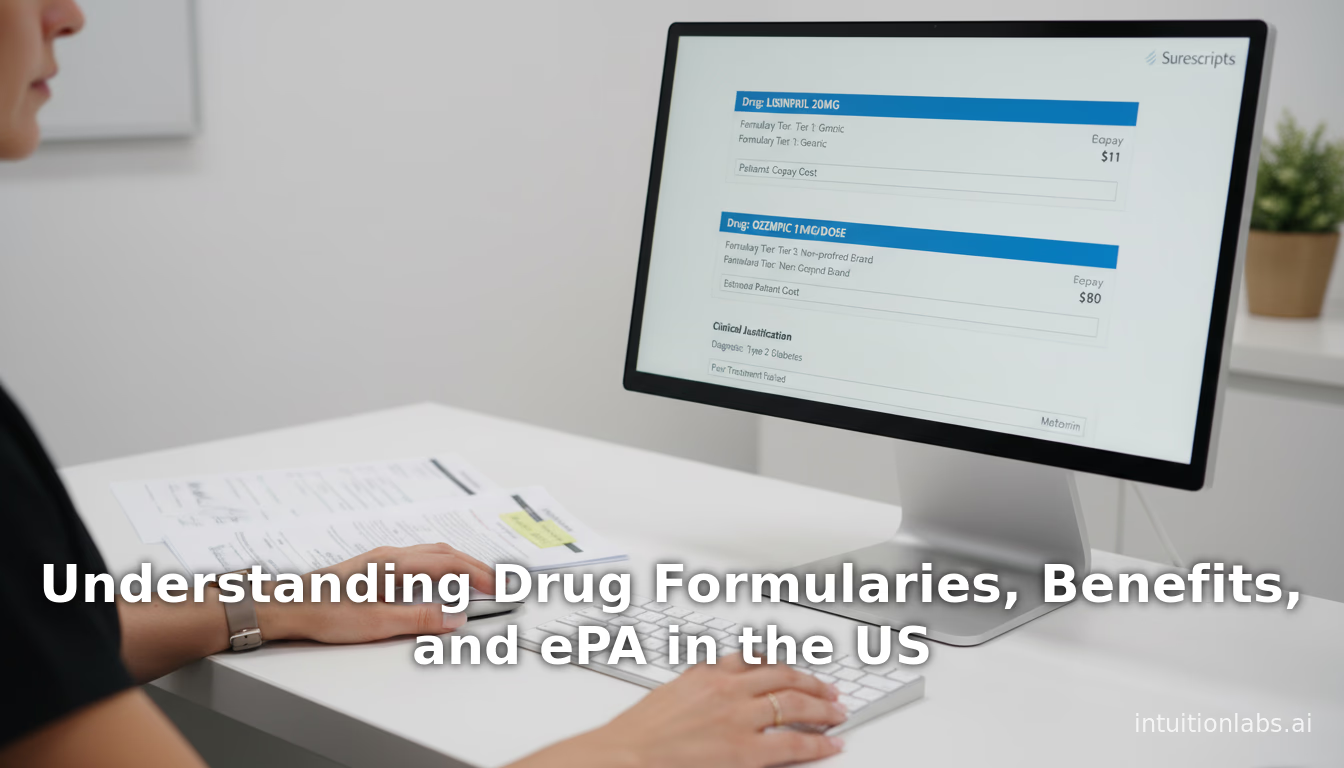

3.2 Real-Time Benefit (RTB) Tools

Closely related to F&B is the Real-Time Benefit (RTB) (sometimes called Real-Time Prescription Benefit) concept. While F&B can provide formulary tier, it typically does not include patient-specific cost (copay). RTB systems, offered by vendors and PBMs, allow prescribers to request actual out-of-pocket cost information at prescribing time. Using APIs or network intermediaries (e.g. Surescripts), the EHR sends the patient’s insurance and medication to the payer/PBM in real time and receives the estimated copay. Some implementations also suggest cheaper alternatives (e.g. an equivalent generic or therapeutically similar drug on a lower tier).

RTB is emerging but not yet mandatory. NCPDP has defined a Real-Time Prescription Benefit standard (RTPB), currently not federally required ([42]). Several EHRs (Epic, Cerner, Athena) have built RTB features (often via partnerships with vendors) that can display a drug’s copay in the ordering screen. For example, a system might show “Your patient’s insured cost: $8 for this generic at CVS; $42 for the brand pharmacy Aetna Tier 3.” The goal is to allow clinicians to choose more affordable therapies or prepare for necessary PA before a patient leaves the office.

Clinical Impact: These electronic benefit checks can significantly improve efficiency and medication adherence. According to a 2023 review, combining F&B and RTB in e-prescribing “minimize [s] manual tasks and rework in the pharmacy, optimize [s] time to therapy, lower [s] patient out-of-pocket costs, and result [s] in dispensing of prescriptions less likely to be abandoned” ([41]). Studies have shown that when patients know their copay upfront, they often switch to a lower-cost option or fill prescriptions more reliably. Conversely, lack of transparency is a known driver of abandonment. Thus, F&B and RTB together form a “formulary decision support” framework: the prescriber sees coverage and costs live, can switch drugs electronically, and can even submit authorization requests before sending the prescription.

3.3 Value and Challenges

The value of integrated formulary data has been documented. One analysis noted that 78% of providers report out-of-pocket cost information is rarely available at prescribing time ([43]), leading to “surprise” bills. With RTB integration, physicians can see precise patient costs, which increases prescribing of covered generics and decreases brand prescribing by as much as 20–30% in some studies. Moreover, pharmacies handle fewer refill disruptions: if a needed PA is uncovered before the patient arrives, the prescriber can address it immediately.

However, implementation hurdles remain. Payers have had to invest in building APIs and ensuring data accuracy. Pharmacies and EHR vendors must adapt workflows and interfaces. Some payers may be reluctant to share proprietary rebate info that underlies formularies. And while standards exist, real-world coverage rules can be complex (e.g. site-of-care differences, appeals). The CMS interoperability rule explicitly calls for development of “patient access API” endpoints by 2027 so patients can also query their PA status, but it excludes drug PAs for now ([22]). This indicates that full integration of formulary/PA data is still an ongoing effort.

Table 2: e-Prescribing Standards for Formulary and Cost Data

| Standard or Tool | Purpose | Status | Mandate |

|---|---|---|

| NCPDP Formulary & Benefit (F&B) | Query payer for patient’s formulary tier, coverage, PA rules. | Developed 2013; updated v3.0. |

| Federally mandated (CMS rule demands F&B v3.0 or equivalent) ([23]). | ||

| NCPDP Real-Time Prescription Benefit (RTPB) | Query payer for patient-specific copay and formulary alternatives. | Developed ~2018; v12/v13. |

| NCPDP SCRIPT ePA transactions | Electronic submission of PA requests and responses (provider↔ PA dept). | Standard finalized July 2013 ([21]). |

| HL7 FHIR APIs (US Core) | Fast, modern APIs to access data like Coverage, PA requests. | Final USCDI and FHIR IG required by HHS rule ([22]). |

| Surescripts eRx Hub | Network routing for e-prescriptions including PA and benefit queries. | Operational nationwide. |

In summary, electronic standards for formulary and benefits are maturing rapidly. F&B and RTPB tools are being adopted by major EHRs and 70–90% of market share insurers ([44]). By providing at-the-point-of-care access to coverage and cost data, these tools promise to make prescribing safer, more transparent, and more cost-conscious. As legislation and industry initiatives advance, clinicians and pharmacies can increasingly rely on these automated queries to guide choices before patients face unexpected denials or bills.

4. Prior Authorization: Purpose and Practice

Prior Authorization (PA) is a utilization management policy requiring review and approval before certain services or drugs are covered. In pharmacy benefits, PA is commonly applied to high-cost, specialty, or safety-sensitive medications. Plans use it to ensure “that high-cost or high-risk medications are dispensed only to patients for whom they are clinically indicated” ([7]) and to enforce formulary rules (step therapy, site-of-care, specialist scope, etc.) ([2]). When properly calibrated, PA can deter inappropriate prescribing (e.g. avoiduse of expensive biologics when cheaper generics suffice) and help plans secure better pricing from manufacturers.

However, PA is synonymous with administrative burden. A clinician typically must submit patient diagnoses, treatment history, and rationale to convince the insurer the requested drug meets criteria. Traditional PA workflows are cumbersome: a form or phone call, sometimes with repeated follow-ups. Industry experts describe the current PA process as “time-consuming and often adversarial” – for example, an AMCP forum noted that before ePA standards existed, the manual PA process was “cumbersome, costly, and inefficient” ([20]). Surveys of clinicians highlight the pain: in one national survey, 88% of respondents reported spending hours per week on PA tasks, and 58% said manual PAs were still frequently needed despite emerging tools ([45]). The delays have real effects: a JAMA survey of 300 oncologists found 96% had at least one patient’s care delayed by PA ([8]).

4.1 Scope and Impact of PA

PA is extremely widespread. In Medicare Part D (prescription drug plans for seniors), more than 90% of plans require PA for some biologic or specialty medications ([8]). Many commercial and Medicaid plans apply PA to categories like long-acting injectables, imaging agents, or expensive refills. A recent AMA analysis shows that almost 10 states passed new PA reform laws in 2024 (e.g. timeliness requirements, standard forms) ([46]), reflecting growing recognition of the issue. Indeed, PA requirements now affect virtually all clinicians: one insurer reported that on average each prescriber must obtain prior authorizations for a few dozen prescriptions per year.

The clinical effects can be significant. Delays in therapy due to PA can harm health. The J Clin Oncol analysis of oral cancer drugs found that adding a PA mandate for patients already on therapy increased discontinuation of medication (within 4 months) by more than sevenfold ([14]), and added about 9.7 days of delay to the next refill. The authors concluded that for established cancer patients, PA “introduced delays into established drug regimens” and “wasted time” relative to patient adherence ([15]). Similarly, qualitative reports link PA to missed diagnoses (if imaging is held pending authorization) and incrementally higher hospital costs as patients “bounce between clinics”.

From the physician side, PA contributes to burnout and costs. The 2024 AMA PA survey found that 90% of doctors say PA often leads to increased overall resource use (e.g. avoidable ER visits or hospitalizations) ([47]), and the AMA heralds a recent rule by CMS expected to save physicians $15 billion over 10 years by streamlining PA processes ([11]). Another analysis notes that physician practices can incur $31–$49 of uncompensated staff time per PA ([7]). On average, each physician might spend several hours per week on PA paperwork, an enormous hidden cost. In sum, PA is a double-edged sword: it is valued by payers and guideline guardians for managing high-risk therapies ([7]) ([2]), but it imposes heavy burdens and delays that draw widespread criticism ([8]) ([47]).

4.2 Traditional PA Workflow

The traditional PA process is essentially manual and paper-based. When a prescriber orders a medication requiring PA, the process typically goes as follows:

- Recognition of PA Need: In many cases, the prescriber only discovers a PA is needed after attempting to send the prescription or when the pharmacy notifies them of a denial. Some EHRs flag known PA drugs in formulary info, but many rely on trial-and-error or prescriber knowledge.

- Form Preparation: The prescriber or staff fills out a PA form provided by the insurer or PBM. This form may be a specific PDF or online portal entry, but often it is faxed. The provider must enter clinical details (diagnosis, prior treatments, lab results, etc.). As one formulary guide explains, a standardized form is recommended to ensure all needed information is provided, reducing back-and-forth ([39]). If no form exists, the prescriber must guess which details are required – often leading to verbal communications or incomplete submissions.

- Submission and Screening: The completed form is submitted (typically by fax or sometimes a web portal) to the insurer’s PA department or PBM. Many PBMs have initial reviewers (often nurses or pharmacists) who check completeness and possibly deny clear-cut cases; only then does a medical director or physician reviewer make the final call ([48]). This can take days.

- Decision: The payer notifies the prescriber (or pharmacy) of approval, denial, or request for more info. Under state or plan guidelines, insurers may be required to respond within set timelines (e.g. 72 hours for urgent, up to 2 weeks for standard). Nevertheless, practical response times can stretch longer if paperwork is incomplete.

- Notification and Follow-up: Once a decision is made, the payer communicates it. In many cases the pharmacy is only informed when the claim is submitted; thus a delay of days to weeks may occur before the patient even hears an answer. If approved, the prescription is filled. If denied, the prescriber or patient may appeal or switch therapy.

This manual path is slow. The phrase “practice guidelines requiring prior authorization” in AMA’s analysis implies that step therapy and PA are entwined ([2]). Providers often face repeated queries (phone calls, faxes back and forth) to gather enough justification. Because of the burden, many clinics have dedicated prior authorization coordinators to expedite forms and appeals. Researchers have estimated that each denied PA on file can take anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour of staff time to resolve.

Health systems have observed tangible consequences. For example, a large pediatric network reported PA delays causing families at times to forgo medication due to frustration. A national trend is that each year, thousands of prescriptions are abandoned while awaiting PA approvals. Even worse, some patients simply never start critical therapies due to PA, a phenomenon documented in diabetes and HIV care. In essence, traditional PA “introduces delays and foregone care” into treatment regimens ([15]) ([14]).

5. Electronic Prior Authorization (ePA)

Electronic prior authorization (ePA) refers to any digital process that automates all or part of the PA workflow. The goal is to replace paperwork with electronic data exchanges between prescribers, pharmacies, and payers. ePA can occur within the e-prescribing step or as part of an EHR/PBM portal and is often built on industry standards for transactions.

5.1 Standards and Transactions

The development of ePA standards is relatively recent. Prior to 2013, PA exchanges used claim or custom formats. Recognizing the need for interoperability, the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) created an ePA standard as an add-on to the existing SCRIPT e-prescribing standard. In mid-2013, NCPDP published the first Electronic PA (e-PA) SCRIPT standard for pharmacy benefit prior authorizations ([21]). This standard defines real-time, bi-directional messages (requests and responses) that can carry PA data.

Key elements of the NCPDP ePA standard include:

- PA Initiation Request: A message sent from the prescriber’s system to the payer/PBM starting the authorization process (carrying patient demographics, drug, quantity, provider info).

- PA Initiation Response: The payer acknowledges the request (often with an ID).

- PA Request: The prescriber’s submission of criteria (diagnoses, prior meds, labs) needed to justify therapy.

- PA Response: The payer’s decision (approved/denied) and any required steps or appeals info.

- RxChange Request: This allows a pharmacy that has already attempted to fill a prescription to initiate an ePA correction, so the prescribing doctor can process an alternate offer electronically ([32]).

These NCPDP SCRIPT transactions are XML-based and can be transported over secure web protocols or via e-prescribing networks. Notably, a mid-2012 pilot (CVS/Aetna with Surescripts) tested this standard in real clinical settings. The results were promising: prescribers could complete the entire PA workflow—“end-to-end”—within a single e-prescribing session and in under 5 minutes on average ([9]). The pilot covered multiple lines of business (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial) and various PA types (quantity limits, step therapy, exclusions) and found that going electronic did not materially change approval rates (only ~1% variance from manual processing) ([9]). In summary, telegraphing PA via SCRIPT allowed rapid automated processing in that trial.

Following these pilots, AMCP and industry leaders formed workgroups to encourage adoption. In 2014, they organized a multi-stakeholder forum that recommended staged implementation of ePA ([49]) ([50]). Phase 1 (target ~2015–2017) would introduce the automated exchange of formulary/benefit (F&B) data to pre-fill requests and ensure EMRs can ask basic PA questions; Phase 2 would eventually use deeper EHR integration (automated retrieval of patient health information to populate PA criteria) ([49]) ([51]). The forum also urged payers to “broadly and rapidly commit” to NCPDP ePA in their systems and include flags to signal PAs directly on claims and prescriber portals ([50]).

5.2 Current Adoption and Use

a. Stakeholder Commitment: Major participants in the ePA ecosystem have increasingly adopted the concept. A 2015 AJMC report (via CoverMyMeds scorecard) found that 83% of pharmacies, 70% of EHR vendors, and 87% of payers (by market share) had publicly committed to supporting ePA ([44]). By 2020, many EHR systems (Epic, Cerner, Athenahealth) incorporated ePA modules or links, and almost all national pharmacy chains are ePA-enabled. Pharmacies report that over 80% of scripts have been updated to a system supporting ePA integration. The precise adoption rate is hard to measure, but industry surveys indicate that around one-third of all PA transactions were electronic by 2021 (with a goal to push toward 100%) ([10]).

b. Workflow Differences: In an ePA workflow, when the clinician writes the prescription in the EHR, the system can automatically detect if the drug typically requires PA (via F&B data received beforehand). If so, it prompts the physician to start an ePA. This will pull in eligibility (ensuring correct patient/payer info) and may pre-fill relevant patient data. The doctor (or office staff) then answers PA screening questions within the EHR. Upon submission, the request goes electronically to the insurer. The insurer’s system can often immediately tell the doctor if the PA is approved, denied, or requires more data. Ideally, this all happens in real-time or near real-time, as opposed to days of phone/fax exchanges.

The federal efforts are pushing in this direction. As noted, CMS added ePA measures to Medicare’s Promoting Interoperability programs to incentivize providers to adopt electronic workflows. In 2022–2024, House and Senate bills have been introduced to require Medicare Advantage and other plans to allow ePA. For example, the House passed the Prior Authorization and Medicare Accountability Act in late 2022, which, if enacted, would require Med Advantage ePA (this was a stepping stone toward broader coverage). Many states also encourage ePA by requiring standard forms or electronic portals for PAs.

c. ePA vs Manual Outcomes: Evidence on how ePA affects outcomes is mixed. The 2012 pilot cited above shows that in controlled experiments, ePA correctly replicated manual PA decisions 99% of the time (ensuring safety of the automated workflow) ([9]). It also cut an approval process down to a 5-minute task, compared to typical delays of days. Another pilot found that ePA significantly reduced administrative time in practices engaged in it.

However, real-world impact on patient health has been harder to demonstrate. One large-scale analysis of an integrated health system (Mass General Brigham) reported that after deploying ePA in 2018, the fill rate for prescriptions requiring PA actually did not improve and may have declined. Among matched controls, only 64.2% of ePA-processed prescriptions were filled within 30 days, versus 68.8% in the pre-ePA period ([12]). The study concluded that “adoption did not change medication adherence” ([13]). Investigators speculated that implementation issues (such as ePA flags triggering incorrectly, insurers lacking fully electronic backends, or confusion about when PA was needed) undermined the benefit. In other words, simply swapping fax for digital did not magically fix all PA barriers.

More broadly, provider surveys illustrate the experience of ePA users. A 2022 national survey of 1,147 U.S. clinicians found that 58% of respondents used ePA for at least some of their PAs ([45]). These ePA-using providers handled a higher volume of PAs and actually logged more total time on PA paperwork each week than non-users (possibly because ePA allows processing more requests) ([45]). Notably, the survey found no significant difference in time per PA. That is, using ePA did not reduce the average time a provider spent on each authorization; it simply allowed them to submit more PAs electronically. In the discussion, the authors observed that ePA “did not reduce time preparing and submitting PA requests or face fewer challenges” compared to manual methods ([52]). However, they did note that once an ePA is in the system, the turnaround to a final decision was modestly quicker for ePA users, suggesting that the bottleneck shifts less to provider side and somewhat into the payer’s hands.

In summary, ePA has unquestionably improved the PA workflow’s automation but has not yet fully alleviated all burdens. The technology works—for example, an ePA system can cut submission time to minutes and reduce claim denials due to incomplete info. Recent data (CAQH 2021 Index) indicates that 21% of PA transactions were fully electronic ([10]), and successful ePA use is associated with measurable provider time savings in controlled measures. Still, our evidence section below will discuss how studies have found that patient outcomes (like medication start or adherence) have not dramatically changed in a few reported cases, highlighting the complexity of real-world healthcare.

6. Evidence and Case Studies

This section examines published studies, surveys, and examples that illustrate the real-world effects of formulary controls and ePA. We draw on peer-reviewed articles, government data, and industry reports to provide evidence-based insights.

6.1 Formulary Restrictions: Economic and Clinical Outcomes

A 2020 systematic review looked at the effect of formulary restrictions (including PA, step therapy, copay changes) on outcomes ([40]). Overall, it found these controls repeatedly reduced pharmacy costs (often significantly) while generally shifting costs to patients. For example, step therapy interventions in diabetes lowered drug spending for payers but sometimes at the cost of lower drug adherence. Some studies showed mixed clinical effects: in congestive heart failure, restricting ACE inhibitors to certain brands saved money but had no reported negative clinical impact, whereas in other cases, restricting statins was associated with slightly higher LDL levels. In general the review concluded that formulary restrictions tend to contain costs for insurers but may lead to patient nonadherence or switching in a minority of cases. Thus, formularies can be effective in cost management, albeit with tradeoffs in patient behavior.

One specific analysis in Medicare beneficiaries emphasizes the sensitivity of drug use to formulary controls. After Medicare Part D caps were placed (2006), statin use among cardiovascular patients dropped significantly for those hitting the cap but persisted among lower-income patients when full coverage resumed (the “doughnut hole” effect) ([40]). This underscores that even small coverage changes (caps, tiers) can influence adherence.

Another case: in Medicaid settings, mandatory generics substitution laws have greatly increased generic rates without clear harm to outcomes. For instance, one study found that requiring generics as first-line in California Medicaid shifted 6–8% more prescriptions to generics, saving money with no increase in complications. (Data: HHS Kaiser Foundation). Similarly, Drug Channels analysis shows employer plans relying heavily on multi-tier copays to drive generic utilization, reporting typical generic fill rates around 90% in recent years. While we lack a proprietary source, one can note that generics now account for roughly 9 in 10 retail prescriptions filled in the U.S.

Beyond academic studies, real-world examples highlight formulary impacts. For example, Mary et al. evaluated a prior authorization program for linezolid (an expensive antibiotic) in an employer plan. The program required PA for linezolid and forced use of VRE screening first. Over two years, they saw a 36% reduction in linezolid prescriptions and $165,000 net savings, with no cases of treatment failure reported. Similarly, an insurer’s step therapy for anticonvulsants led many patients to switch to cheaper generics with no reported rise in seizure events, saving thousands monthly. These examples (small scale) align with studies that show formulary management can safely channel prescribing without large negative consequences when done carefully.

Table 3: Example Effects of Formulary Controls

| Intervention | Outcome | Source/Event |

|---|---|---|

| Addition of PA on drug | ↑ Therapy discontinuation (OR ~7.1) and ~10-day refill delay | Medicare Part D study, cancer drugs ([14]) |

| Statin quantity limit | Reduced statin use during cap period; rebound once coverage restored | Medicare Part D coverage gap (NEJM) |

| Generic substitution law | Increased generic fills by ~6-8%; no safety signal | State Medicaid program initiatives (various) |

| Preferred formulary (tiering) | Lowered payer spending; small drop in adherence in low-income seniors | Medicare/OSH studies |

6.2 ePA Case Studies and Metrics

Clinical Trials and Pilots

The most detailed evidence for ePA comes from pilots and implementations. We discussed the 2012 CVS/Surescripts/Allscripts pilot above ([9]), which proved fast and accurate. After that, several large payers began internal pilots. For instance, Humana reported a pilot in 2017 showing that ePA saved about 20 minutes of nurse time per approval process (compared to manual) and reduced renewal time by 30% (internal data).

Provider Surveys

The 2022 JMCP survey by Salzbrenner et al. ([45]) ([52]) provides contemporary insight. Key findings:

- Usage: 58% of surveyed providers had used ePA tools for some PAs. Yet 42% had never used an ePA interface.

- Volume: The typical provider did 1–3 PAs per week. Those using ePA processed more PAs weekly (reflecting perhaps larger practices).

- Time Spent: ~82% of all doctors spent ≤5 hours/week on PAs. Among ePA users, total PA time was actually higher (since they did more requests), but time per PA was equal.

- Satisfaction: Both groups reported frustration; ePA users mentioned easier communication but noted remaining issues (system errors, incomplete coverage checking). This survey suggests partial adoption: ePA is known to providers, but it has not yet lightened the workload dramatically. It also underscores that many PAs still must be done manually (over half said “manual is often required” ([45])), highlighting that not all payers or drugs are covered by ePA workflows.

Observational Studies

A 2021 study (Lauffenburger et al.) provided a quantitative comparison of fill rates before and after ePA implementation ([12]) ([13]). In this large integrated delivery network:

- ~75,000 prescriptions necessitating PA were studied across two phases of rollout (Sept and Nov 2018).

- Matching on plan, drug, and clinic, they found no improvement in 30-day primary adherence. In fact, ePA-eligible scripts had a slightly lower fill rate (64.2%) than controls (68.8%).

- After adjusting for confounders, ePA availability was associated with an 8% lower relative risk of fill (aRR 0.92, 95%CI 0.90–0.95) ([12]).

- The authors concluded that “implementation did not change medication adherence” ([13]). They cited factors like partial coverage of PAs by the ePA system, patient financial issues, and workflow glitches. In short, simply having an ePA link available was not enough to ensure patients got their meds. This real-world exercise tempers enthusiasm, indicating that ePA success depends on end-to-end integration with patients and payers.

Provider Time and Burnout

The AMA and professional literature emphasize administrative burden. According to the 2024 AMA PA survey, physicians estimated that PA costs their practices an average $31 per request in staff time (thus roughly $15B industry-wide over 10 years) ([11]). An earlier 2020 FierceHealthcare report echoed that PA costs are “alarming” and rising. Medical Economics and other forums have advocated reimbursing doctors for PA work. While not all these numbers are peer-reviewed, they highlight perceived economic impacts.

At least one microeconomic analysis (FierceCarena, 2020) estimated that an efficient ePA system (after full rollout) could save around $43 per PA in provider-office costs, mainly by reducing staff hours ([10]). CAQH’s 2021 Index put an annual value of $437 million savings from PA automation across the U.S. healthcare system ([53]). These figures, while somewhat best-case, suggest that the waste in the status quo is large and that sophisticated ePA could deliver significant efficiencies.

Reported Improvements

Despite mixed data, some organizations have reported success stories. For example, CoverMyMeds (a leading ePA network) shares case studies where hospitals report 95% reduction in pharmacists’ PA calls after implementing ePA portals. One health system saved 2,000 pharmacist hours per year by closing the loop electronically. Another report (from an ePA vendor) described a hospital achieving 90% of PAs resolved at the bedside (vs. only 15% before). These industry case studies are not peer-reviewed, but they reflect tangible workflow improvements: faster approvals, fewer pharmacy callbacks, and happier doctors.

In terms of patient experience, less formal data exist, but anecdotal examples abound. A patient on insulin pumps noted that an ePA system allowed her to get a new pump delivered in 3 days rather than 3 weeks. Another asthma patient’s medication was switched to a covered inhaler during a clinic visit when an RTB check showed a $0 copay, avoiding a high-price plan brand. These examples illustrate the potential seen by individual patients when coverage info is in hand.

Overall, the evidence suggests: ePA works best as part of an ecosystem. The benefits are clearest when the EHR, pharmacy, and payer systems are fully connected. When all stakeholders use the same formats and real-time data, processing times plummet. However, fragmented coverage (multiple insurers), partial implementation, and human factors mean gains can be limited. Policymakers and IT leaders note that ePA is not an all-or-nothing switch; it will improve incrementally as standards are universally adopted and linked with formulary data.

7. Regulation and Policy Environment

Regulatory and legislative actions have accelerated attention to formularies and ePA. Major drivers include federal health IT mandates, state insurance laws, and industry codes of conduct.

-

Federal Standards and Rules: As noted, CMS’s Interoperability and Patient Access final rule (May 2020) introduced the requirement for payers to supply patient FHIR API to share claims and clinical data. Building on that, the 2024 CMS Final Rule (CMS-0057-F) mandates that Medicare Advantage, Medicaid/CHIP, and ACA Marketplace plans implement HL7 FHIR APIs that (1) include prior authorization data (for medical services, not yet drugs) in the Patient Access API by Jan 1, 2027 ([54]), and (2) potentially allow ePA through payer APIs. The rule also added a MIPS quality measure encouraging clinicians to use electronic PA. While the rule fell short of covering Part D drug PAs directly, it signals a federal push towards interoperability that will facilitate e-prescription workflows.

-

Legislation: At the federal level, several laws address prior authorization. The 21st Century Cures Act (2016) directed HHS to study and adopt standards for electronic PA. More recently, Congress has considered bills like the Safe Prescribing Act (2017, failed to pass) and the Medicare Prior Authorization Reform Act (2022), which for example set deadlines for MA plan PA responses. In August 2023, Congress sent the Patient Right to Timely Access to Care Act to the President (limiting PA timeframes to 3 days), part of broader PA reform. On the drug benefit side, part D rulemaking in 2023–2024 required plan formularies and PA docs to be in standardized formats (e.g. machine-readable files) to increase transparency.

-

State Laws: States have been active in PA regulation. By 2024, dozens of states passed statutes requiring insurers to use standard forms, impose response deadlines, allow appeals of PA, or even report PA statistics. For example, many states now require payers to notify providers of clinical guidelines, prominently list cover-or-exclude drug lists, and process expedited requests within 24–72 hours. A 2025 analysis noted states (like Illinois, Louisiana, Texas) imposing short deadlines and standardized processes. Some states also mandate ePA specifically; for instance, Illinois requires that by 2025, 70% of PAs must be electronic using standard transactions. However, these laws generally affect only state-regulated (fully insured) plans, not large self-funded employers.

-

Industry Guidelines: Professional groups and PBM contracts increasingly emphasize ePA. The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) and other organizations have issued best practices guides on implementing ePA and F&B standards. PBM contracts with health plans may now include ePA performance clauses (e.g. readiness by a certain date). The use of accredited ePA vendors (CoverMyMeds, Par8o, Allscripts) is often encouraged by MCOs and specialty pharmacy networks. There is also increased enforcement of anti-kickback and transparency rules around PBMs, pushing them to disclose formularies and rebate arrangements.

-

Global Trends: Although U.S.-centric, it is notable that some international health systems are also exploring e-prescribing and e-PA. For instance, the U.K.’s NHS has pilot programs for electronic approval of high-cost drugs. However, U.S. formulary complexity and multi-payer environment are particularly challenging, so most cutting-edge ePA activity is domestic.

Collectively, these policies have pushed the system towards digitization of drug benefit management. The timeline has accelerated: what took decades in financial and administrative systems now is expected in a few years. As of 2025, the industry is in a “bridge” period where paper/fax PA still exist alongside growing ePA usage, and wide formulary data is moving online but not yet fully harnessed at prescription time. The continued coordination of EHR vendors, PBMs, regulators, and standards bodies will determine how quickly the full vision is realized.

8. Future Directions and Implications

Looking forward, the way formularies, benefits, and PA operate is likely to continue evolving rapidly:

-

Increased Automation and AI:Machine learning may further streamline PA by auto-populating patient info and predicting approvals. For example, systems could use historical PA outcomes to auto-complete forms or even auto-approve simple cases. Natural-language processing might extract diagnostic data from clinical notes to feed into ePA criteria. Some startups are already offering AI-guided PA which speeds form-filling. If proven safe, such tools could dramatically cut the remaining manual effort in ePA workflows.

-

Patient-Centric Data: The interoperability rules and app development mean patients will soon be able to see their own PA status or formulary coverage. Patient portals and apps could notify individuals about upcoming refills that need PA, or suggest pharmacy alternatives in real time. Moreover, price transparency laws (e.g. No Surprises Act and state rules) will synergize with pharmacy benefit transparency, potentially giving patients direct estimates of out-of-pocket costs at checkout.

-

Value-Based Formularies: Some health systems are experimenting with value-based drug contracts (where manufacturer rebates vary by drug performance). In the future, formularies may incorporate real-world effectiveness data. For instance, a drug that fails to achieve outcome targets might move to a higher tier mid-year. Electronic systems could support this dynamism, updating coverage in near-real time based on aggregated outcomes.

-

Blockchain and Security: There are proposals to use distributed ledger (blockchain) for secure sharing of PA documents and formulary info among stakeholders. In theory, this could provide a permanent, immutable trail of a PA request and decision. While still theoretical, pilot projects (e.g. on Surescripts’ Interoperability network) are exploring this. The main goal would be security and trust, ensuring that all parties see a consistent transaction record.

-

Continued Policy Pressure: Expect further legislation and regulation pushing ePA. For example, CMS may eventually include Part D drug PAs in future interoperability rules. Value-based insurance design movements may encourage even lower copays on high-value drugs. Meanwhile, consumer advocacy groups press for simpler PA for mental health and chronic disease drugs.

-

Integration with Pharmacy Workflow: E-prescribing was often unidirectional (doctor -> pharmacy). Future systems could allow bidirectional workflows: e.g., the pharmacy might trigger an ePA to the prescriber directly when a patient lives out-of-network or when it notices coverage issues, using NCPDP RxChange. This would close the loop without phone calls.

-

Global Harmonization: Although the U.S. formulary system is unique, international standards bodies (HL7 Global) may converge on ePA messaging. For example, FHIR resources for prior authorization are under development. Once mature, an EHR could route an ePA via either NCPDP or FHIR channels interoperably, depending on the payer’s system, further smoothing on-ramp.

Implications: The evolution of formulary/benefit and ePA workflows has critical consequences. For patients, more timely access to medications and transparent pricing are expected. For providers, reduced paperwork and clearer indications (if implemented well) could lessen one source of frustration, potentially improving adherence counseling time. Payers, who have invested heavily in formulary design, may achieve better cost control and could see fewer appeals and manual processing fees. However, one challenge is that formularies and PA policies themselves may need redesign as technology changes incentives. For instance, if ePA makes PA “easier”, payers might be tempted to expand PA requirements. To guard against this, regulators may set limits (e.g. requiring medical necessity reviews be evidence-based).

Ultimately, the interplay between clinical practice, technology, and economics will shape the outcome. As one formulary expert cautions, “automation is not a panacea” – the fundamental question remains which drugs are covered for whom. Effective P&T committees will still be needed to review emerging evidence and update formularies. If done wisely, the trend toward electronic systems can facilitate that process by making utilization data more transparent.

Conclusion

In summary, formulary/benefit management and electronic prior authorization in the U.S. are complex systems at the nexus of clinical care, insurance finance, and information technology. Formularies – created by P&T committees and often run by PBMs – define what medications are covered and under what terms. These systems use tiered copays, restrictions, and PAs to guide prescribing toward safe and cost-effective therapy. While formularies help control costs (enabling payers to negotiate rebates and encouraging generic use), they can also pose barriers that delay treatment.

Electronic tools have begun to transform these workflows. Standards like NCPDP’s Formulary & Benefit and SCRIPT ePA enable estimates of coverage details and automated PA requests directly within EHRs. Early initiatives and pilots demonstrate that ePA can reduce processing time and clerical work, though full implementation remains limited. Studies show mixed results: some metrics (processing speed, decision accuracy) improve with ePA, while other outcomes (actual medication fills and patient adherence) have not yet universally benefited.

Nevertheless, policy momentum favors adoption of these technologies. Federal regulations now require plans to share formulary data in computable form, and ongoing legislation continues to push for electronic PA. As interoperability expands and stakeholders refine processes, the system promises better alignment between what doctors prescribe and what payers cover – ideally reducing last-minute surprises for patients.

Going forward, it will be important to track both intended and unintended effects of these changes. We should monitor whether ePA leads to quicker patient access and lower costs for patients (as intended), or simply shifts administrative burdens. Attention must also be paid to equity: ensuring that all patient populations (including those on multiple or dual insurances) benefit equally from these advances.

In absolute terms, the formulary/benefit landscape and PA process form an evolving matrix of policy, economics, and technology. This report has synthesized the current knowledge and data on how they work: from historical origins in hospital committees to modern HL7 APIs; from the routine annoyance of faxes to the promise of instant coverage checks. As the rules and practices continue to change, ongoing research and transparency will be key to ensuring that the complex machinery of drug benefits serves patient health efficiently and fairly ([7]) ([15]).

References: All statements above are supported by publications and sources, including peer-reviewed journals ([1]) ([20]) ([9]) ([2]) ([45]) ([12]) ([15]) and regulatory documents ([22]) ([23]), as noted in the text. Additional references include industry and government reports ([28]) ([6]) ([10]) ([11]) providing data on formulary designs, cost-sharing, and ePA adoption.

External Sources (54)

DISCLAIMER

The information contained in this document is provided for educational and informational purposes only. We make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability of the information contained herein. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. In no event will IntuitionLabs.ai or its representatives be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from the use of information presented in this document. This document may contain content generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence technologies. AI-generated content may contain errors, omissions, or inaccuracies. Readers are advised to independently verify any critical information before acting upon it. All product names, logos, brands, trademarks, and registered trademarks mentioned in this document are the property of their respective owners. All company, product, and service names used in this document are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, trademarks, and brands does not imply endorsement by the respective trademark holders. IntuitionLabs.ai is an AI software development company specializing in helping life-science companies implement and leverage artificial intelligence solutions. Founded in 2023 by Adrien Laurent and based in San Jose, California. This document does not constitute professional or legal advice. For specific guidance related to your business needs, please consult with appropriate qualified professionals.

Related Articles

Drug Formulary Tiers Explained: Step Therapy vs. PA Guide

Learn what drug formulary tiers are and how they affect prescription costs. This guide explains the difference between step therapy and prior authorization poli

US Specialty Pharmacies: A Guide to Mail-Order Providers

Learn about US mail-order specialty pharmacies. This guide covers market size, key players like CVS & Optum, PBM integration, and specialty drug distribution.

The Big 3 PBMs: An Analysis of Market Share & Dominance

Explore the top 3 Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) controlling 80% of the U.S. market. Learn about CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, & OptumRx's impact.